An Unexpected War Story

A World War II internment in Sweden leaves indelible memories, but they're not the ones we usually hear about. Jan-Olof Nilsson documents them in his latest film, Lucky Strike: When the Americans Came to Our Village.

-

The Hicks Crew with their bomber, 1945. Signed in 2015 by pilot Roget Hicks and nose gunner Bob Birmingham. Image: Jan-Olof Nilsson

The Hicks Crew with their bomber, 1945. Signed in 2015 by pilot Roget Hicks and nose gunner Bob Birmingham. Image: Jan-Olof Nilsson -

-

I was very impressed by the energy of Bob Birmingham when I met him on Feb. 15 at an event near his home in Greendale, WI. At age 90, he is an example of what we all hope to be should we be lucky enough to reach that age. I don’t know whether he has a secret for living with such vitality, but if the way he survived the war in 1945 is any indication to how he’s lived out his life, this is but one great story in his long life.

-

Bob Birmingham shows special memorabilia to his good friend, author and filmmaker Jan-Olof Nilsson.

Bob Birmingham shows special memorabilia to his good friend, author and filmmaker Jan-Olof Nilsson. -

-

“It was January 1945, I was 19 years old,” began Birmingham at the presentation of the documentary, “Lucky Strike,” in which his story is told. “I was in the right place an the right time.”

-

Swedish filmmaker Jan-Olof Nilsson, already working on his next project.

Swedish filmmaker Jan-Olof Nilsson, already working on his next project. -

That place was Sweden — though he didn’t immediately know it when he parachuted from his B24 bomber before it crashed into a farm field. “I represent the 1200 airmen, from 33 planes, whose lives were saved by being able to make it to Sweden,” he said. They had been damaged while flying over Germany and needed to land their war-torn planes, so they headed in the direction of safety, not knowing where they’d land. Or if they’d land.

-

Jan-Olof Nilsson introduces his documentary, Lucky Strike: When the Americans Came to Our Village, to a large crowd at a veterans' event in Greendale, WI. The documentary premiered on Swedish television in May 2015 in celebration of the 70th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe.

Jan-Olof Nilsson introduces his documentary, Lucky Strike: When the Americans Came to Our Village, to a large crowd at a veterans' event in Greendale, WI. The documentary premiered on Swedish television in May 2015 in celebration of the 70th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe. -

Birmingham’s crew jumped from their plane before it crashed, while the residents of Rättvik, Sweden heard — and saw — the sputtering plane above. Jan-Olof Nilsson’s father, who was 10 years old in 1945, had been outside playing “Cowboys and Indians” with some friends when they heard the noise in the sky and saw parachutes dropping into a nearby farm field. The kids rushed there on their bicycles.

-

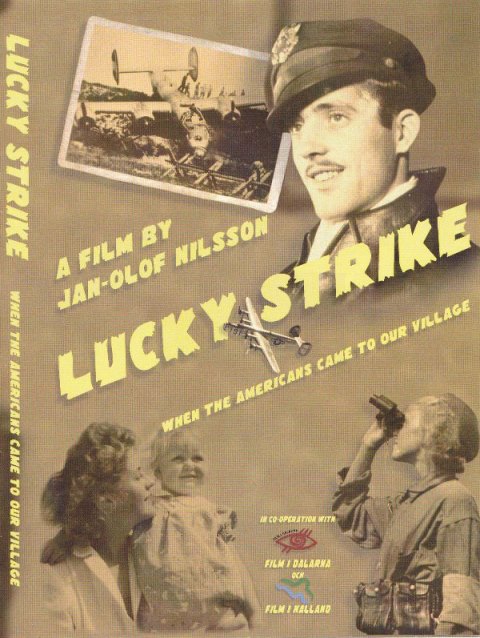

Lucky Strike documentary cover art.

Lucky Strike documentary cover art. -

And from that moment, Rättvik was changed. The lives of the American airmen were changed. Sweden took good care of the airmen: “The government provided us sanctuary,” said Birmingham, “and the Swedes themselves joyously received us into their communities.” The Americans felt welcomed and part of the towns they lived in, dancing together on the weekends, skiing in what Birmingham recalls was a “winter wonderland paradise.” Relationships developed with the locals, and by the end of the war, many had girlfriends to say good-bye to and wives to bring back to America.

-

Bob's son, Greendale village president Jim Birmingham, proudly shares details of his dad's story.

Bob's son, Greendale village president Jim Birmingham, proudly shares details of his dad's story. -

Bob Birmingham never saw his plane again, though it was his job to repair planes while he and the others worked in Sweden until the end of the war. The Americans were interned in Rättvik, Gränna, Främby, Västerås and Falkenberg.

-

World War II veteran Bob Birmingham eagerly talks about his experiences in Sweden during the war in 1945.

World War II veteran Bob Birmingham eagerly talks about his experiences in Sweden during the war in 1945. -

Everyone who lived in the small towns that hosted the Americans seemed affected by their presence. And for decades, Nilsson grew up hearing all kinds of stories about these airmen from his father, who himself grew up to be a pilot. He had to find out for himself what really happened, so Nilsson, who still lives in Falkenberg, began a research project that culminated in a wonderful friendship with “Uncle” Bob Birmingham — and this documentary.

-

WWII memorabilia from Sweden.

WWII memorabilia from Sweden. -

In 1995 in England, a reunion of WWII airmen brought together a lot of veterans — and Nilsson. There, the son of the Swedish pilot met the Wisconsin airman who fell from the sky 50 years earlier. That started an unlikely friendship that, two decades later, has been the foundation of several visits in each other’s countries, and many conversations about experiences during the war. Birmingham did learn a little Swedish while he lived in Sweden and easily recalls a couple important phrases: “Tack så mycket” and, blushing a little he said, “Of course I can say, Jag älskar dig.”

-

When I met him near a table full of memorabilia, I asked whether there was anything in particular — an item, a memory or tradition — that he made sure to bring back to the States when he returned from Sweden. He rushed over to the table and picked up a straw wreath to show me. It was actually from 1997 when he and his wife traveled to the site where he dropped from his plane. The land is still owned by the family who ran the farm during WWII, and they met the farmer. Unexpectedly, the farmer showed them a door of the barn which somewhere along the line was replaced with the exit door salvaged from Birmingham’s Flying Fortress B24. That was the only piece of the plane he has seen since 1945. The farmer directed the Birminghams to the area where Bob fell to his safety … and it’s the grasses from that spot which made the wreath they hang on their Christmas tree every year. How very Swedish.

-

By Amanda Robison

-

-

-