Wearable art from Norway

White flowers are bursting open on a cobalt blue background and the waist is slightly cinched with a knitted midsection in two shades of pink, making this, like all Oleana sweaters, look like a painting. Oleana is definitely art. Art you can wear.

-

Oleana founder and managing director Signe Aarhus surrounded by (left) her assistant Torbjørg Grøttveit and (right) Laura Almaas, one of Oleana's U.S. representatives.

Oleana founder and managing director Signe Aarhus surrounded by (left) her assistant Torbjørg Grøttveit and (right) Laura Almaas, one of Oleana's U.S. representatives. -

-

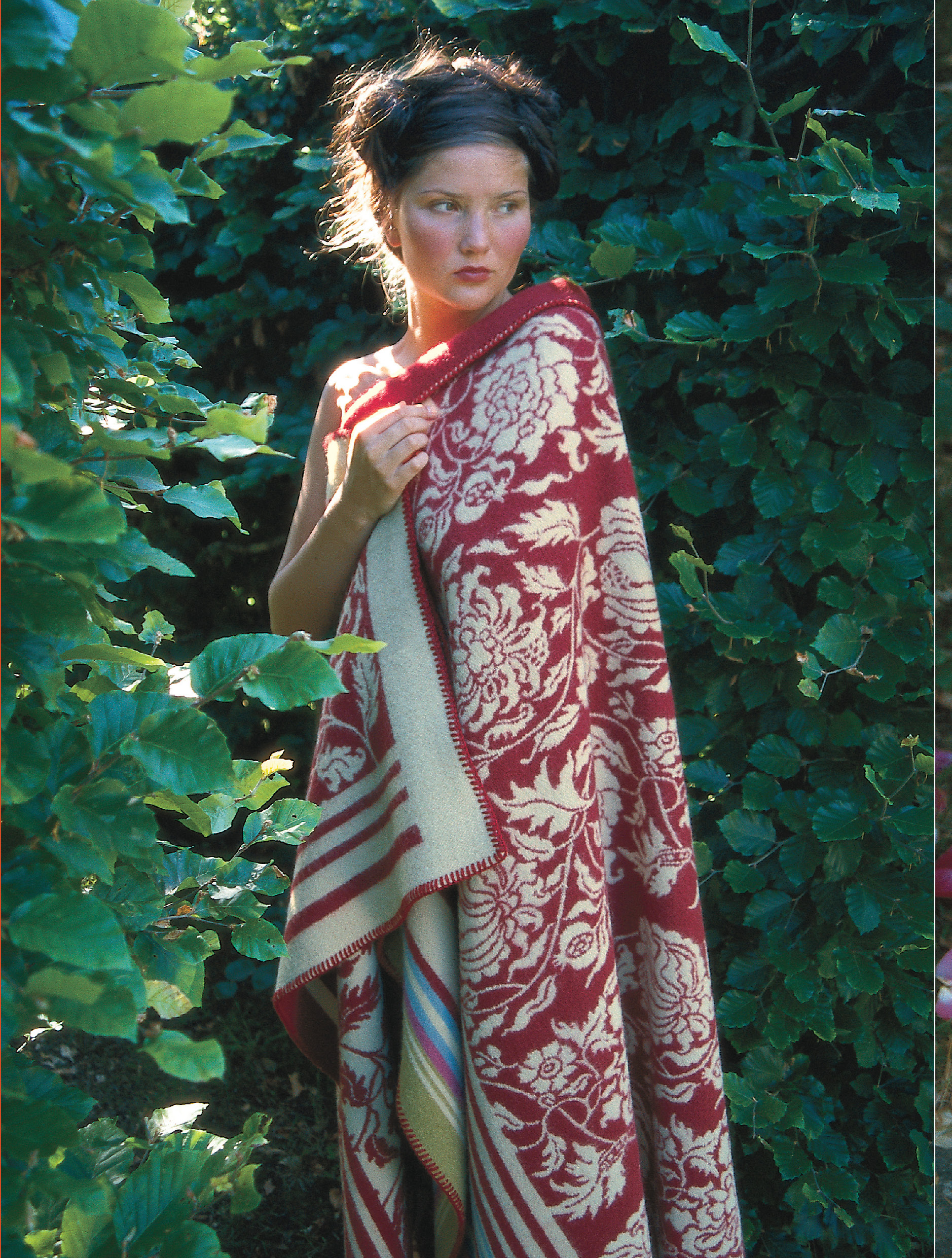

What initially draws one to Norwegian Oleana’s sweaters and blankets is of course visual—with such splendor and colors, how can it not be?—but wrap yourself in one of those sweaters or tuck your child into one of the blankets and what you will also be doing is making a subtle life style choice. By buying Oleana you’ll support women through this company which doesn't outsource; you'll support a company that will probably help reduce your carbon footprint. You’ll most definitely get loads of compliments.

-

-

-

Signe Aarhus and Kolbjørn Valestrand founded Oleana 18 years ago in defiance of the growing outsourcing of what had once been a rich Norwegian textile tradition.

“We wanted to sell good design,” explains Signe when I meet with her at a café in the Ansonia building in New York City, “but we also wanted everything to be produced in Norway—not China—and to this all banks said ‘No!’ It was very difficult to get financial backing.”

Signe and her husband Kolbjørn prevailed, though, and they eventually offered their house as a guarantee. Finally they had enough capital to survive that first crucial year.

“We broke even the second year and made money the third,” Signe continues. “But making money, a lot of money, was never our prime concern, we wanted to have a meaningful life for us. Good design is not a result of compromising. It’s like art.”

In the meantime they also found a treasure trove in artist and designer Solveg Hisdal, who today does all of Oleana’s design.

“She had an exhibition and we went and saw it and decided right away that she was the one we needed.” -

-

International yet Norwegian

Although it’s easy to see the Norwegian heritage in Hisdal’s designs, Signe explains that folk art in general is more international than we tend to believe.

“Countries and cultures have always borrowed from each other. The silk in the Norwegian folk dresses, the bunads, was imported, for instance. And Solveig’s been following the silk road and found inspiration from places as far away as China. Some of her patterns are inspired by the German Meissner porcelain, so it’s not all that Norwegian.”

Yet the Norwegian knitting tradition is strong, and has an important place at Oleana. Pattern knitting, still quite rare in the U.S., is easiest done with circular needles, a strong Norwegian tradition not as common in other Nordic countries.

“The bunads were all about competition,” Signe explains. “It was all about who had the prettiest dress. When the church didn’t allow for too much color or embroidery, women got clever. They’d wear sexy red underskirts that would not be seen while they were seated, but that would be seen while they danced.”

Little things like that is what Oleana is all about: subtle but beautiful details. A button is never just a button—it’s pretty, it has a history. There are patterns on the insides of the sweaters which can only be seen by the one who wears it, unless she folds it a bit to reveal it. Though Oleana’s design are inspired by textiles and patterns from the past they still have a distinct modern feel, something Michelle Obama has also recognized. While her husband picked up his Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, the First Lady picked up a couple Oleana sweaters. -

-

Feminism in practice

A little film featuring the background and design of Oleana shows the factory that turns Solveig’s designs into sweaters. We see women working hard by the machines, but we also see them laughing and chatting, and when somebody turns on the music they dance.

“Is it always so much fun at the factory?” I ask Signe.

“No,” she says with a smile. “Because whenever you work with people you’ll have confrontations, it’s inevitable you know. But we try to. Look, we have 60 people working in the factory and we have 5 stores—all in all we employ more than 75 people. And few of our employees leave us because we try to focus on the human aspect of things. We know it’s tedious work, working at those machines. So once a year we close the factory and take all our employees on a trip.”

Together they’ve been to Spain where they took flamenco and wine courses, they’ve been to Istanbul and to Italy, where the yarn used in Oleana’s sweaters is spun.

“I see these trips as my own, personal feminist projects,” says Signe. “Many of the women who work at our factory had never traveled by themselves when they came to us, they had never really been in charge of their own passports. That was something they left to their husbands. It feels great to see these women take off from husbands and children and homes. To teach them to travel by themselves, to show them how things work, they all know how the subway in London works now. It’s important that they have these trips to look forward to, when daily life at the factory gets boring. It’s important that we all feel proud of our profession.”

Oleana also has an amazing profit-sharing philosophy, sharing 35-40 percent of it equally between them all, the rest of which goes to buying and the upkeep of machines, the shareholders and capital tax.

“This is to illustrate that in our company,” says Signe, “everyone’s important.” -

-

Bright future ahead

Oleana’s goal was never to make anyone a millionaire, something that might be a bit difficult to grasp in an age when it’s all about quick cash. It was never about mass-producing either. Oleana has never advertised (a trick they learned from The Body Shop). Says Signe:

“Our sweaters aren’t cheap (they retail at an average of about $400), but we want to teach people that they need less but more beautiful clothes. It’s better to buy one beautiful item that you can wear for a long, long time than a lot of cheap stuff that you end up not wearing more than once anyway. This is in keeping with the ecological movement, too. We should all buy less.”

Oleana sweaters and blankets are made of ecological wool, silk and alpaca, and you can dress them up with jewelry and a pretty skirt, or dress them down with a pair of jeans. A customer once said:

“Wearing an Oleana sweater is like having a dog—it’s a great ice breaker, a great conversation piece.”

So what’s next for the company?

“We’re interested in combining culture with business. Oleana has had major fashion shows at the Grieg Hall in Bergen, Norway as well as at the Womens Club in Minneapolis, MN. We’ve also exhibited at the Nordic Heritage Museum in Seattle, WA, and the Goldstein Museum of Design in St. Paul, MN, among other places. But for the future my dream would be to combine a new factory and contemporary architecture to make a cultural tourist industry center with a beautiful rose garden and sheep. We’d serve Norwegian food and unite all our ideas in one building. A place where we could have both art and music, that sort of thing. That would be wonderful. I could sit in that garden and spin. I am a very good spinner, you know!” -

-