Sweden sets up shop at the 1915 fair

Swedes come from everywhere to celebrate their new landmark in San Francisco.

-

The Ferry Building relit to celebrate the centennial. Photo: Ted Olsson

The Ferry Building relit to celebrate the centennial. Photo: Ted Olsson -

-

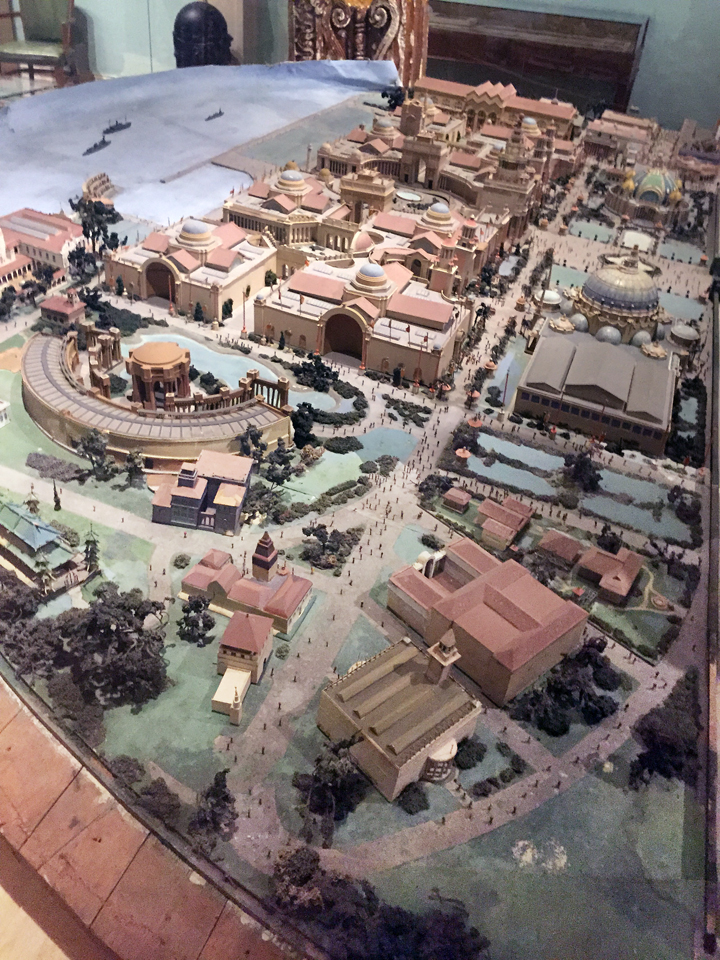

In early March 2015, the California Historical Society opened its exhibit, “The Jewel City,” the moniker of San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915. This is a wonderful display of memorabilia from that time, with two distinctive exhibits. One is a model of the 1915 main fair grounds done for San Francisco’s 1939 world’s fair. This very large model (how is such a rarely used display stored?) provides a helpful perspective of the beautiful and monumental central third of the grounds with its palaces and courtyards, fountains and triumphal arches. [www.PPIE100.org]

The other distinctive exhibit, free to all at night because it is creatively projected onto the windows of the museum, shows magnified photos of the fair. This display will continue into May and shows the work of half a dozen photo artists. It also shows the splendor of the architectural elements and their lighting. -

Swedish pavilion (foreground) in perspective, PPIE 1915. Photo: Ted Olsson from CHS "City Rising" exhibit

Swedish pavilion (foreground) in perspective, PPIE 1915. Photo: Ted Olsson from CHS "City Rising" exhibit -

-

The fair was novel for its daytime colors and its nighttime illumination in 1915. It was transformative in many areas and distinguished in the history of world’s fairs. In addition to the art and cultural displays, those emphasizing transportation (befitting the opening of the Panama Canal) and the marvels of electricity were foremost.

About half a dozen regional dams were harnessed to supply the daily and backup electricity for the fair. And it was lavishly expended, for the mundane operations of the fair grounds and for public transportation to/from the fair. Many earlier fairs had used electricity to a much lesser extent and always for mundane operations, but this fair used it to create complete factories for Ford, Levi's and Hearst’s SF Examiner.

Before the 1906 earthquake, the city had but half a dozen streetcars and two competing streetcar companies. By the time of the fair, the city-monopolized Muni (municipal transit) had dozens of street cars, numerous lines and even tunnels to reach through the hills connecting outlying areas. With both its hotels and mass transit electrified, the city effortlessly accommodated and transported millions to the fair. This year, for the duration of the centennial, the Muni Museum features its exhibit, “Fair, please.” [www.streetcar.org/museum/]

This was also the first world’s fair to illuminate its monumental central section as well as accentuate its gateway and other attractions. The architects had created stunning buildings and its sculptors formed monumental statues and fountains, all impressive. -

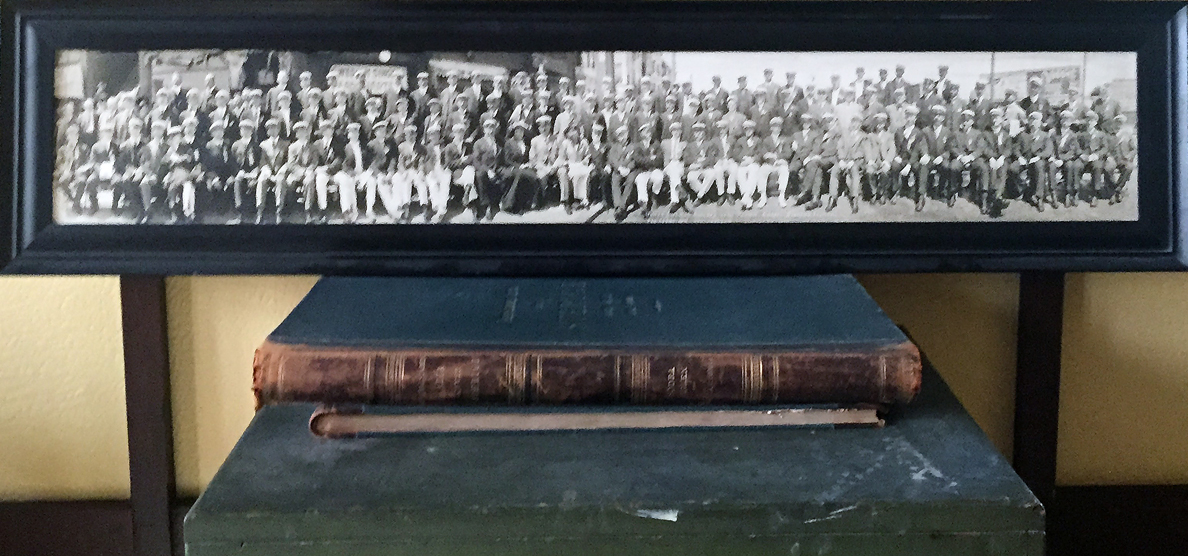

Union of Swedish Singers. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC)

Union of Swedish Singers. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC) -

An illuminating exhibition

All this would have been dark had it not been for Walter D’Arcy Ryan. He was the first director of General Electric’s new Illuminating Laboratory. Willis Polk, chief architect of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), felt that all details had been accounted for before this dapper engineer, visionary and consummate showman appeared unknown before him to offer an opportunity that was beyond imagining: “Mr. Polk, I am going to illuminate your Exposition!” Polk agreed to allow him half an hour to present his proposal before the whole committee of architects. When Ryan finished speaking to them four and a half hours later, having convinced all, he left with the title of PPIE Chief Illuminator.

This was the first time subtle floodlighting — “washed with light” as Ryan termed it (rather than spotlighting with searchlights) — had been used. He inconspicuously located all the lights recessed in the architecture or behind bushes, banners or columns. At night the statues and fountains beamed — the huge columns in the fountains of The Rising Sun and the Setting Sun (apparently marble during the day, then metamorphosed at night into two torches of internally illuminated frosted glass) — gardens glistened, the broad avenues were illuminated for safety as well as comfort, and the monumental palaces were magnified. Even the pools for the first time shimmered at night with concealed, submarine light. And the Tower of Jewels sparkled with all of its Novagems.

PPIE historian Laura Ackley makes her point: “The number of searchlights used at the Exposition was greater than all those owned by the U.S. Army and Navy combined in 1915.” She adds that the daily requirement of 5,000 kilowatts — costing $830 per day (equivalent to $19,600 in 2012) — was enough to light a contemporary city of 200,000 people.

But Ryan reserved his brilliance for some of the most spectacular special effects. Not merely were the exteriors illuminated, but so were the interiors — “The Light Within,” he called it; this greatly expanded the time (and money) people could spend at the fair.

All world’s fairs aim to offer a vision of the future, so General Electric displayed all its electric appliances and conveniences for the home, and onsite factories demonstrated them for the workplace. The Great Scintillator projected a rainbow of colors into the night sky, and when there wasn’t enough fog, Ryan had a steam locomotive below the arc lights to generate the appropriate steam screen. In presenting Ryan with the Grand Award for Iliumination, the Expo’s Jury reflected popular opinion: for the first time recognizing illumination itself as a decorative art. -

Swedes drive in style to Swedish Pavilion, PPIE 1915. Photo: Ted Olsson

Swedes drive in style to Swedish Pavilion, PPIE 1915. Photo: Ted Olsson -

Ferry Building lights up

During PPIE 1915, when many came to the city by ferry, the city’s iconic Ferry Building, a survivor of the 1906 earthquake, was illuminated as a beacon to beckon visitors to the world’s fair. So, on March 3, 2015, the city held a centennial ceremony with a festive dedication at this attraction. Since everyone has so enjoyed the light show currently playing on the western span of the Bay Bridge’s suspension cables, PPIE memorabilia-collector Donna Ewald Huggins had the bright idea (and the financial responsibility) for raising donations to recreate the effect this year.

Huggins introduced many dignitaries and the primary philanthropist, Ted Taube, who made this re-creation possible. Anthea Hartig, leader of PPIE 2015, and author Laura Ackley provided perspective and musicians set the mood. With the arrival of dusk, Mayor Lee, former Mayor Willie Brown and other notables pulled the old-fashioned switch and suddenly the Ferry Building tower was lit prominently proclaiming the year 1915. -

The Swedish Pavilion at 1915 world's fair. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC)

The Swedish Pavilion at 1915 world's fair. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC) -

Dedication of the Swedish Pavilion

In its March 4, 1915 edition, the local Swedish newspaper, Vestkusten, reported on the inauguration of Sweden’s Pavilion at the PPIE, on which this article heavily depends. On Tuesday, March 2, 1915, the weather was as auspicious as the day, and Swedes throughout the San Francisco Bay Area congregated at the Swedish American Hall for a caravan to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. That afternoon, a long line of cars festooned with dual flags of Sweden and the United States left the hall and wended through the city along a prominent route.

Arriving at the fair grounds, the local Swedes organized themselves into a grand parade with a float bearing a queen and her court — a tableau recreated at every one of their Swedish Midsummer festivals since San Francisco’s first world’s fair. According to Vestkusten’s account, more than 5,000 people marched to assemble for the inauguration of the Swedish Pavilion. One can only imagine the drama of the moment: such a huge assemblage, all speaking Swedish and parading through the most beautiful monumental buildings and gardens, among fountains and statues. Rounding the nostalgic Palace of Fine Arts, they marched down the Avenue of Nations to their distinctive Swedish Pavilion.

In front of the grandstand, a chorus of the Union of Swedish Singers sang and Fylgia’s male drill team, in sharp uniform, gave the occasion proper solemnity. And among all the Vasa organizations here, Fylgia’s fluttering silk banners made it festive. The local congress of clubs, the Swedish-American Patriotic League (SAPL) and the local Swedish-American Exposition Committee (SAEC) were responsible for all planning, programs and promotion of the Swedish Pavilion. All the Swedish churches and their congregations in the Bay Area turned out, as did all of the Swedish folk musicians and folk dancers, and their families. Everyone in provincial costumes distinguished the occasion. Even Swedish-Americans not associated with any particular club turned out in force to join the parade and celebrate their dual patriotic pride. -

Parade group in Swedish Pavilion courtyard. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC)

Parade group in Swedish Pavilion courtyard. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC) -

Crowd of 10,000

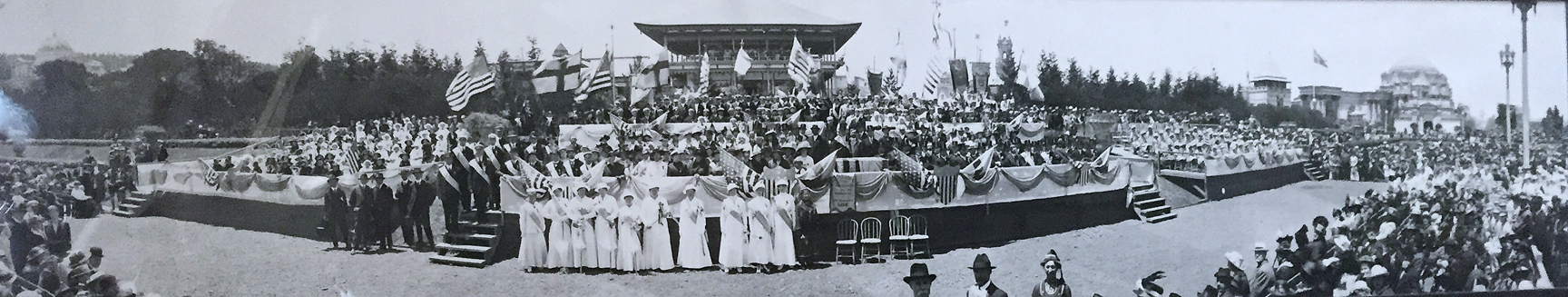

Vestkusten estimated that dignitaries on the grandstand were viewing a crowd that had swelled “certainly [to be] very close to the 10,000 mark,” which, it reported, demonstrated “Mother Svea’s power over her children in the diaspora. What a sight!”

Assembled on the grandstand along with Sweden’s Commissioner General for the pavilion, Richard Bernström, Art Commissioner Anshelm Schultzberg and Consul General in San Francisco William Matson, were other dignitaries to speak to the assembled, including congressmen, mayors and William Lamar, who had helped swing the federal vote for location of the fair from New Orleans and to San Francisco. Also there were a large number of commissioners from the other foreign and state pavilions, together with many consuls from these 27 countries.

As a brisk breeze fluttered the twin flags of Sweden and the U.S., Commissioner Bernström, speaking in English, greeted his countrymen to vigorous applause for a very moving speech dedicating the building. And right on cue, the expo’s daring aviator, Lincoln Beechey, flew his monoplane over the crowds, dropping down a flurry of small, silk Swedish flags.

A cordial greeting from Sweden’s King was offered with compliments to the local Swedish-American Exhibition Committee for its dedication and hard work in completing this wonderful pavilion. Because Sweden’s funding for this fair was larger than for any previous expenditure, Bernström hoped that Sweden would continue such investments and develop closer relationships with the U.S., particularly now that a steamship united both countries.

At the conclusion of the ceremonies, Bernström ushered dignitaries into the pavilion. There Vestkusten was able to speak with San Francisco’s distinguished Swedish architect and local managing architect for the pavilion, August Nordin, in whose opinion Sweden’s pavilion was the finest among all the European pavilions. He especially appreciated Sweden’s displays on steel and Rorstrand’s china. And Vestkusten evidently agreed, citing the interior as “truly a jewel box, replete with all Sweden has achieved.” The newspaper appreciated the generous support for this project but noted that the achievement was the result of the care, commitment and work of the local Swedes, including Commissioner General Bernström, noting that “his right hand must have been very sore” after welcoming each person that day.

That night Commissioner Bernström hosted a banquet for no less than 350 guests — for all the organizations and individuals who had contributed so much to creating the Swedish Pavilion. Held at “The Old Faithful Inn,” located in the exposition area, the head table was understandably very long. Smaller decorated tables wore Swedish colors and both flags were draped about. At the conclusion of the banquet all were invited to the theater at the base of the hotel for a concluding ceremony. -

Inaugurating the Swedish Pavilion at grandstand, PPIE 1915. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC)

Inaugurating the Swedish Pavilion at grandstand, PPIE 1915. Photo: Swedish Cultural Heritage Foundation of Northern California (SCHFNC) -

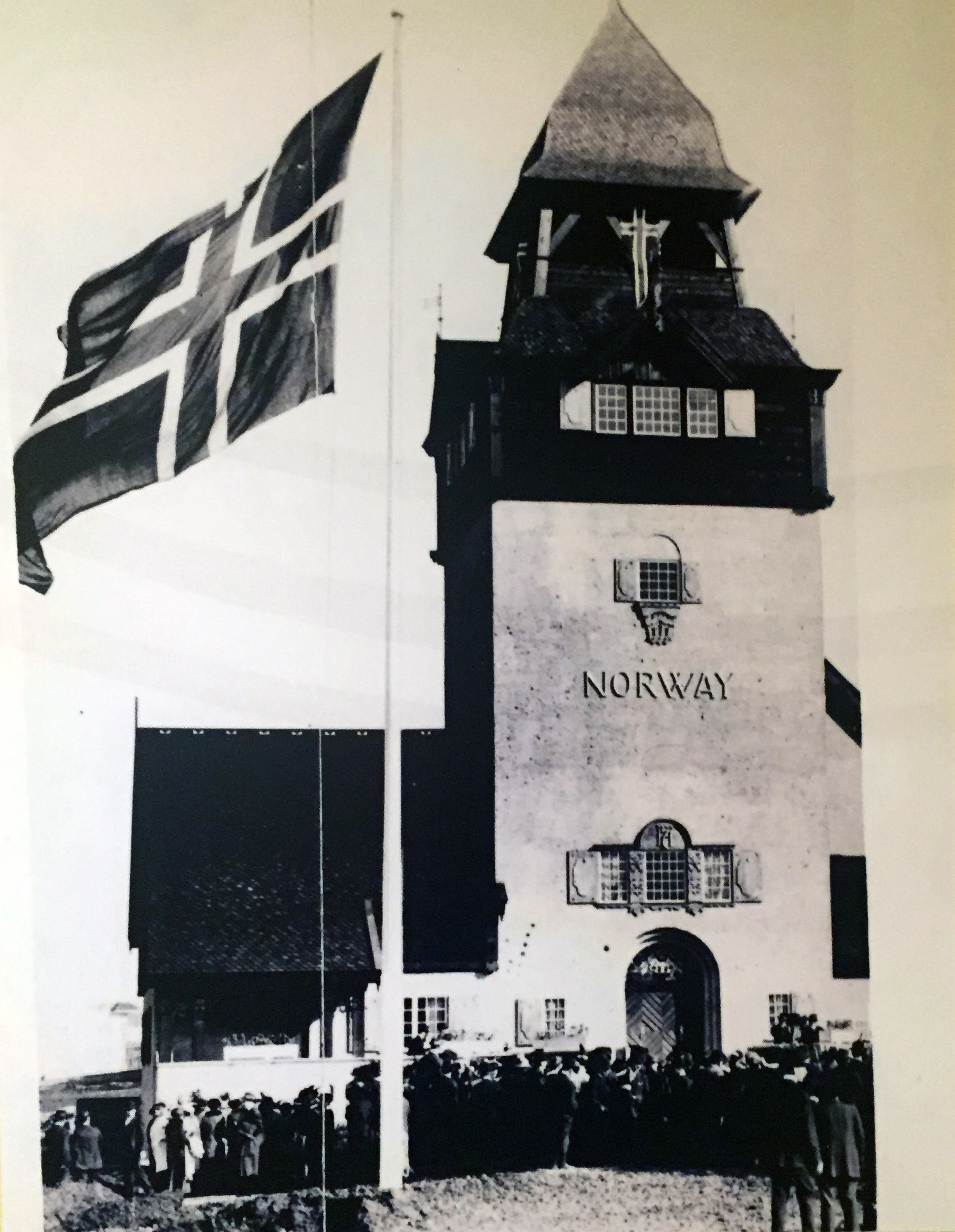

The Norwegian Pavilion

Earlier that week Norway dedicated its pavilion, “witnessed by a couple of thousand Norwegians and several other Scandinavians and other visitors.” After a musical flourish by a military band, Norway’s Commissioner Gade recalled the importance of Norway in world history and Norwegians’ enterprise in the Americas, where their numbers rival those in the homeland. After the dignitaries spoke, the emcee concluded by thanking all his countrymen for funding the building and invited them into the big building with its tall staved tower. However, he apologized that the interior of the building was not nearly complete. Located on the site that was originally Sweden’s, the pavilion was obscured from the main boulevard by France’s massive French palace (a smaller replica of the Palace of the Legion of Honor), so that only the tip of Norway’s tower was seen from the central Avenue of Nations. -

Richard Bernström, Sweden's Commissioner General, Swedish Pavilion, PPIE1915.

Richard Bernström, Sweden's Commissioner General, Swedish Pavilion, PPIE1915. -

And that’s the way it was.

-

Norway's Pavilion at PPIE 1915. Photo: Ted Olsson from CHS "City Rising" exhibit, PPIE100

Norway's Pavilion at PPIE 1915. Photo: Ted Olsson from CHS "City Rising" exhibit, PPIE100 -

By Ted Olsson

-

-