Sveadal battles California forest fire

After nearly a century of heritage and devotion, recent celebrations were followed by two long weeks of dread.

-

The sky threatens as the fire creates its own fire clouds and weather. Don't miss another important event in Swedish America (Sweden or, of relevance to Swedes in the United States) <a href="http://www.nordstjernan.com/subscribe" target="_blank">Subscribe to Nordstjernan</a> and Make Life Sweder!

The sky threatens as the fire creates its own fire clouds and weather. Don't miss another important event in Swedish America (Sweden or, of relevance to Swedes in the United States) <a href="http://www.nordstjernan.com/subscribe" target="_blank">Subscribe to Nordstjernan</a> and Make Life Sweder! -

-

The Swedish American Patriotic League and its Sveadal cabin owners gathered at the Clubhouse for the Closing Day Dinner on the last Saturday of September, marking the close of Sveadal’s summer season. The event recognized what it takes to run Sveadal during the summer and on special occasions. Everyone was alerted that next year would be one of substantial transition, since several stalwarts who had given so much to the community would be retiring from their positions to resume their busy lives. So, this would be the year for new volunteers to fill large shoes for the good of the community.

Kirsten Baughman, summer manager and member of Sveadal’s Board of Governors, offered an extensive list of gratitude for all the many volunteers who filled their roles this year. Karen Parks, who for many years had handled off-season rentals, would be turning over her duties, as would Kathleen (Poonie) Erikson, who for more than a quarter century had managed the bar and annual presentations of photographic history of the community.

As in any organization or large property, it is always remarkable — yet often unnoticed — that so many people are needed to keep an institution vital. It is important to get young people involved early, to mentor them but also have them ready to step in whenever someone can no longer continue at a job. No one that Saturday night imagined how soon the new, younger generation would be called upon to take charge.

At this dinner many people were celebrated and thanked for their contributions. Many others were asked to volunteer. Families were recruited to prepare and serve our traditional mid-week dinners. In the spring there would be the usual work weekends to prepare for visitors. In the fall there is always a work weekend to manage the water pipes and hydrant system and make sure the infrastructure is ready. That last exercise, too, was prematurely tested.

It was a convivial evening after which people retired to their cabins or drove home to their surrounding cities. Other than half a dozen winter residents, cabin owners locked the doors on their cabins, not to return until next summer or only for special events during the fall and winter. -

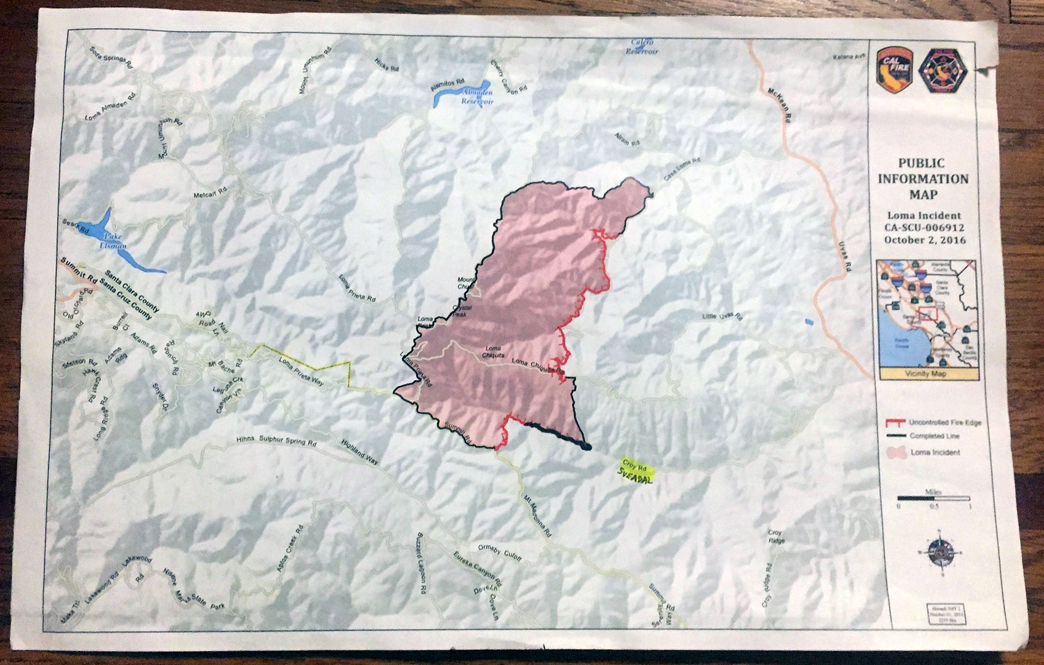

Loma Fire with Sveadal just beyond the spear point on right. Black line indicates containment; 2 red lines were not yet contained at the time of writing.

Loma Fire with Sveadal just beyond the spear point on right. Black line indicates containment; 2 red lines were not yet contained at the time of writing. -

-

Fire storm closes in

The stubborn Soberanes wild fire had been raging on the other side of the mountain since July. Many firefighters had been brought in from other counties to battle it, but the coastal range is thickly forested on both sides, thriving on fog from the Pacific Ocean.

The grave risk of forest fires is well known throughout the state. The number of fires has been increasing annually as has the acreage burned and the cost of fighting them. The drought had desiccated the ground, the trees, the surrounding vegetation. Although wildlife is hearty in the hills, many animals were moving lower to forage and drink. The creeks and tributaries were trickling down the watershed.

The following Monday afternoon, September 26, the Sveadal community learned from television and radio reports of another fire, sending up social media alerts among us all. A helicopter headed for the Pacific side of the mountain spotted a one-acre fire just beginning near the summit — where stand several wealthy homes and a swarm of radio and television transmission towers, along with vital federal and state emergency communications equipment.

Sveadal is located in Uvas Canyon, a heavily forested box canyon flanking Loma Prieta peak, the epicenter of the notorious 1989 earthquake. Santa Clara County’s Uvas Canyon County Park consists of 12,000 acres at the end of Sveadal’s road. Adjacent to the park but on the other side of the creek above and beyond Sveadal, the Open Space association was looking at setting aside property for a wilderness area. And below Sveadal, the four-mile long and winding two-lane Croy Road parallels Uvas Creek and connects at a T-junction with Uvas Road, which is about 10 miles long with very large reservoirs at either end; they are now both quite low.

At 1,000 feet above sea level, Sveadal is nestled between two creeks. Alec Creek, a tributary of Uvas Creek, is boulder strewn with tree limbs and other debris scattered along its path from winter torrents. And Swanson Creek gained some fame during the spring when visitors clogged the roads to see its waterfalls. Both lose their potency as summer wears on, though Uvas Creek has never run dry in recorded history.

These creeks were important in Sveadal’s founders’ decision of locating the Swedish retreat here. Even then, old burned-out stumps were witness that forest fires had visited this land. And during the preceding 50 years, Sveadal and Uvas Canyon had experienced half a dozen fires.

And now the fire that was gorging on the trees was evaporating any water in its path. So, the creek was holding onto its reputation with but a trickle.

All the news that night and the next was about this Loma Fire which had quickly spread from a couple acres to more than 1.5 square miles along these rugged hills, 30 miles south of San Jose and 10 miles northwest of Morgan Hill, a bedroom community for high-tech companies.

The fire quickly created its own weather system and fire cloud over the summit, visible throughout Silicon Valley. The huge cone of smudged smoke encircled at its base by the bright orange-yellow band of flames could be seen as though a volcano were erupting. Hundreds of homes had to be evacuated Monday night and more residents were ordered to leave as the flames continued to spread overnight.

The fire was only five percent contained. At this point Cal Fire (the state’s wildfire-fighting agency) and Santa Clara County were also mobilizing all available personnel and equipment to control the fire on hillsides parched by low humidity and surrounding temperatures in the upper 90s. By Tuesday the houses on the ridge had been consumed and the news reports were broadcasting scenes of torched trees and homes turned to ashes along the peak, except for the transmission towers, which stood on a barren spot of the peak. -

A Fire tanker drops retardant across the hills.

A Fire tanker drops retardant across the hills. -

Preparing for the worst

As they saw the menacing flames rising higher and racing toward them, three local Sveadal couples — the Parks, Baughmans and Masseys — feared for their lives. They had removed all of Sveadal’s historic memorabilia to a safe place, inspected all the cabins and turned off all propane tanks. As they cleared out, they left a poster at the entrance to Sveadal, thanking firefighters and notifying them that everyone had evacuated, together with maps of the community’s cabins and water supplies. The clubhouse was open for them if they needed it.

With the fury of the fire getting closer, they took what might be their last look at Sveadal, after almost a century of heritage and devotion. They raced down the four miles of winding canyon road and together looked back, the night sky was flaming orange and the huge fire cloud reflected the fury of the insatiable fire. They had escaped with their lives; the fire fighters had quit for the day, and now these Sveadal couples could only witness the destruction. They had fled to safety but they imagined the wildlife dashing as best they could to outrun the fire illuminated in that smoky night by the fire’s glare.

Cal Fire and the sheriff, fearing looting, soon had to limit those entering Croy Road. Emergencies are by nature confusing. PG&E electric utility company sprayed fire retardant on critical utility poles, but a commercial tree cutting service they had hired for the season was determined to earn their fee, fire or no fire, until finally ordered to quit.

On Tuesday, with permission from the sheriff and Cal Fire, only Ryan Massey, Sveadal’s “Fire Chief” Rob Green and Steve Peterson, who was in charge of the water system and knew all of the hydrants, were allowed to return. This was fortunate, for while some local Cal Fire crews knew the layout of Sveadal, other visiting firefighters did not have accurate information. The trio was able to inform them that Sveadal was a community of homes, not a campground, and located previous firebreaks on the property as well as hydrants, pumps and other materials. They could also indicate the condition of each cabin and which were defensible. They offered our 50,000 gallons of water in storage bladders and 20,000 in the swimming pool. Later several other Sveadal residents dropped by to help this authorized crew.

Another Sveadalian, Eva Brolin Urdiales, a member of the Board of Governors, became extremely important to our efforts. As a bio-chemistry teacher with military emergency medic training, she became the community’s liaison with all the leaders among the fire and county officials. One of the best aspects of her liaison experience was meeting these leaders who respected her own expertise; they told her one of the most important aspects in fighting a fire is having a face to put with a community — it makes a huge difference in how they fight it.

Meeting with them daily at dawn and dusk, she was able to inform them of our efforts and to report back to our governors on the progress of fighting the fire. She met three female firefighters, and she made her own mark at these meetings of the top leaders of the firefighting team.

Eva admired how professional the fire command camp was. There are several sets of top state commanders, about 50 to a team, to handle all aspects of the job, both fighting the fire in 24-hour shifts, informing officials and the public. She witnessed that the firefighters’ camp is really a complete city; there is nothing the camp lacks for the fire fighters, for communicating with emergency resources, nor for informing the journalists. All of it professionally managed.

She was also impressed with the extent of local, regional, state and federal resources quickly and professionally assembled to manage fighting the fire, although the corollary is that even with all agencies on the management leadership team, we must limit our contact with officials so they can focus on the fire.

Of course, our community’s leaders had first-hand knowledge both of the progress of the fire and of the firefight. So, between Eva’s reports from the command center and Ryan’s “fireside chats” onsite, the Sveadal community remained thoroughly informed.

The first days established the perimeter of the fire. Fire leaders knew they must protect our rugged canyon. By the time they got to Sveadal, they knew where all of our resources were located. They also knew where they to go to create the firebreaks.

Throughout the days and into the nights almost a thousand firefighters were battling for every inch of land. They had fire trucks and other equipment wherever passable. Crews with bulldozers and chainsaws cut swaths of barren firebreaks and then set backfires to burn anything near these roads, creating a moat of safety. From their perches on roofs and the clubhouse, our personal ground crew witnessed a dozen planes and helicopters commute continually from reservoirs to douse the fire. The planes could carry 1,200 gallons of water. A flying tanker, carrying 12,000 gallons of fire retardant traversed the mountain, dumping its load on the fire as well as on Sveadal to protect it.

One marvels at the pilots and planes circling the flames to drop water or retardant on it, but we don’t often think of how heavy water is (a gallon of water — a bit more than a cubic foot of water — weighs eight pounds; aerial fire tankers fly at about 300-400 feet high; of course water falling from that height will reach a terminal velocity but the mass of the water falling from that height can be crippling). -

Flames and smoke from far off hills are seen through the trees.

Flames and smoke from far off hills are seen through the trees. -

At the mercy of weather

By Wednesday 300 homes were threatened as the winds battered the fire down the slopes of the canyon on the eastern flank of the Santa Cruz Mountains. By now the fire had grown to 3.5 square miles and was but 10 percent contained. However, some evacuations were lifted as the weather began to aid the firefighters struggling to save hundreds of structures still in the path of the fire. Soon the fire was 22 percent contained, after charring more than 6 square miles. It was not expected to be extinguished before the next week.

Fortunately all day Thursday the fire command ordered the strategic defensive effort of a final huge fire break to be constructed about a mile downwind from that day’s fire. This road would be bulldozed from accessible Nibb’s Knob on one side of the mountain in a broad swath across multiple valleys to the other. Manpower and equipment were deployed, felling everything in their path to cut a two-lane dirt road into the hillside. Then, in a controlled burn, they torched all the underbrush between them and the wildfire, hoping to control the fire well short of this, but if not, this would be the last stand. By the end of the day, they had hewed out this tremendous firebreak.

By the end of Thursday, the official report stated that the fire had destroyed eight homes and a firefighter was sent to the hospital after a waterdrop hit him and broke his leg. But cooler weather and additional firefighters and equipment joining the battle gave hope that the fire might be controlled by the end of the week, though gusts of wind up to 35mph were forecast for Friday afternoon. By now the fire was 34 percent contained and had consumed 6.5 miles, threatening 325 structures in Santa Clara County.

Whereas the fire had apparently started at a human encampment on a very hot day without much of a breeze, and continued under hot, windless conditions, the forecast for Friday suggested there might be northwest winds, driving the fire further down the various canyons, isolating many fire crews. At night the firefighters must rest, not merely from exhaustion but because the dark of night is too perilous for the personnel. However, through the darkness, the nightwatch tracks the advancing flames. All hoped the cooler weather of night might hamper the fire, but large wildfires such as this create their own weather. As the hot air ascends without water into the night, it chills and can then fall not as rain but rather creating its own windstorm, which can accelerate the flames to new fuel.

The firebreaks had been the focus on Thursday, because commanders were so concerned with the wind predicted for the next day. Friday morning realized the fears of the previous day. The forecast north winds did indeed blow and the surrounding weather did not slacken the fire with any hint of rain. Now, having jumped the paved road of Loma Chiquita, the winds turned the fire in a new direction, easterly. Finding fresh stands of timber and kindling, it began to race down Uvas Canyon, outrunning the creek that had carved the canyon.

Friday was the scariest day, when the wind drove the fire to consume the tinder and kindling of the hillside together with giant redwoods, oaks, manzanita and laurels. Despite the best efforts of firefighters, the fire jumped upper lines. In four hours it raced more than a mile down Uvas Creek’s canyon, gulping acres by the minute. The heat of the inferno together with the spray of embers torched everything in its path. Even the parched timbers that had sequestered carbon and secured the hillsides for a lifetime were set afire, as the flames galloped across the crowns of the trees’ canopy.

After the wind was predicted to shift, more firebreaks were created accordingly, leaving two firebreaks guarding Sveadal: One was in the County Park and a second firebreak was just beyond the park. Because of this Eva and the firefighters were confident Sveadal could be saved — and though the broad Nibbs Knob firebreak did not stop the fire, the one at the creek did. This is where the firefighters had to stand fast. At the end, the line held and they were able to stop the fire within barely a mile of Sveadal.

The firefighters had saved Sveadal but were now fighting the fire on other fronts. Friday evening’s report claimed that the blaze, which was but 50 percent contained, had razed 4,345 acres, burned 28 structures (including a dozen homes), and threatened an additional 325 structures. Cal Fire battled this wildfire with 2,104 firefighters from all over the state, six air tankers and 16 helicopters.

By the weekend the firemap showed that the northern and western perimeters of the fire had been contained, as had the apex of the Uvas Canyon portion of the fire, saving Sveadal at the tip of this spear-point of fire. On the south there remained a relatively small inglenook of fire. And above the Uvas Canyon triangle, a large front, about half the length of the fire was being fought.

For all practical purposes the Loma Fire had finally been corralled and Sveadal residents were allowed to return briefly to retrieve cherished belongings as fire trucks rumbled back up the road.

The professional term “containment” means a fire is confined behind a border where it might be spreading. Only when the perimeter of the area has both a firebreak (40-feet-wide or four bulldozer blades wide) and an additional burnback of 300 feet of scorched but inflammable earth, is a wildfire considered to be contained. So only when that perimeter is complete is the fire claimed to be 100 percent contained. Yet it may take a couple more weeks, as in our case, before the fire is extinguished. And only then can fire investigators go in to discover the cause of the fire.

It wasn’t until October 12 that the Loma Fire was declared 100 percent contained. In the next article, read about the results, records and lessons learned: Part 2 of Sveadal battles California forest fire The forest wildfire rerouted this couple's planned Sveadal wedding reroutes: Capella Wedding: same time, different place -

Fire burns the hills, the sky is smoky at midday,breathing is hard.

Fire burns the hills, the sky is smoky at midday,breathing is hard. -

By Ted Olsson, San Francisco

Photography: SAPL, Sveadal -

-