Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective

This is the first in a series of articles on Ingmar Bergman, his films, his troupe and his significance.

-

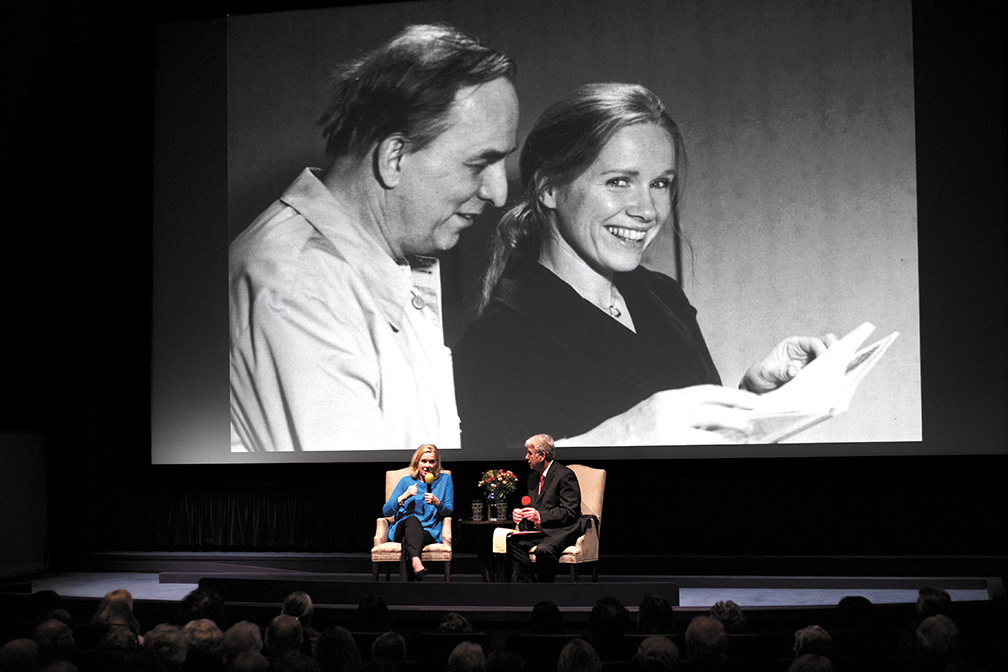

During the first week of February 2018, Liv Ullman inaugurated the yearlong Bergman100 festival of films at the Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA, Berkeley) and at the California Film Institute (CFI, San Rafael). Photo: Tommy Lau

During the first week of February 2018, Liv Ullman inaugurated the yearlong Bergman100 festival of films at the Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA, Berkeley) and at the California Film Institute (CFI, San Rafael). Photo: Tommy Lau -

-

Ingamar Bergman, a giant of cinema in his day, his reputation has only increased since his death a decade ago. The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA or PFA) are conducting one of the largest worldwide celebrations of this phenomenal artist with a year-long showing of almost all of the master’s 71 films. Of course he was also renowned for theater and television productions. PFA is an appropriate site for this celebration with its exhaustive research archives.

-

Inauguration of the Bergman100 festival at both PFA & CFI. It was an honor and great pleasure for Ted Olsson to interview Liv Ullmann on her illustrious career. Photo: Tommy Lau

Inauguration of the Bergman100 festival at both PFA & CFI. It was an honor and great pleasure for Ted Olsson to interview Liv Ullmann on her illustrious career. Photo: Tommy Lau -

-

In early February I had the privilege to interview the actress Liv Ullmann who was in town for the centennial celebrations of Ingmar Bergman. The celebration began in the Barbro Osher Theater at PFA; Ms. Ullmann’s visit was sponsored by both the Norwegian and Swedish Consulates, by the Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation and Norway House.

At the reception Ullmann remarked that it is so wonderful that Ingmar is now recognized worldwide for his creativity in film: as producer, director and author. He never believed in heaven, but she hoped that somewhere he can marvel in the respect and recognition afforded him during this year of his centennial, The Year of Bergman. Following the reception the still daring film Persona was shown, with comments before and after the film by Ullmann. A similar format has been followed at the California Film Institute (CFI) of San Rafael, where on several occasions she answered many questions from her adoring fans. -

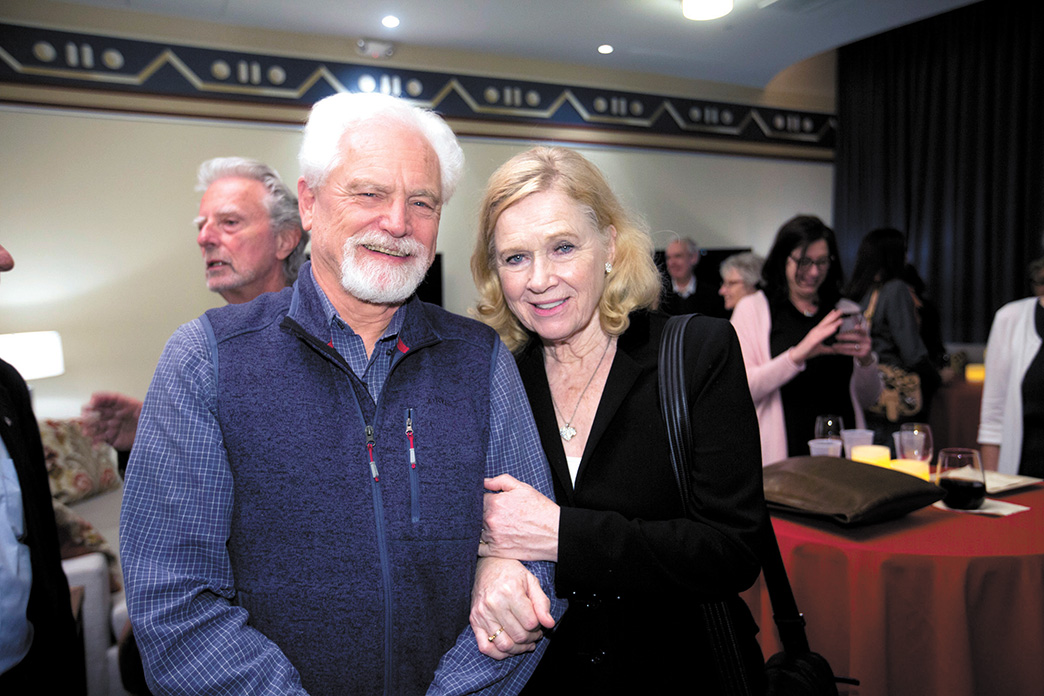

Liv Ullman initiated the beginning of a year of Bergman films at the PFA and CFI, sponsored by the Consulate of Sweden and the Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation. Gathered here (L-R) are: Richard Peterson (CFI), Susan Oxtoby (PFA), Liv Ullmann, Barbro Osher, and Dr. Donald Saunders, husband of Liv. Photo: Tommy Lau

Liv Ullman initiated the beginning of a year of Bergman films at the PFA and CFI, sponsored by the Consulate of Sweden and the Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation. Gathered here (L-R) are: Richard Peterson (CFI), Susan Oxtoby (PFA), Liv Ullmann, Barbro Osher, and Dr. Donald Saunders, husband of Liv. Photo: Tommy Lau -

Bergman’s muse

It seems most appropriate to begin this series by interviewing Liv Ullman, Bergman’s love, muse, actress and chosen director. Born in Tokyo to Norwegian parents, she lived in Canada and the U.S. during WWII and returned to Norway late in the 1950s to act in film and theater. After meeting Ingmar Bergman in 1965, he cast her in a starring role with her friend Bibi Andersson, in the landmark film, Persona. On the set of this first film they fell in love, and Bergman told Ullman on that spot on Fårö island he would build a house for them - which he did. He also predicted to her: “You and I are painfully connected.”

While Bergman had four marriages with half a dozen children and many lovers, Ullman was a constant presence in his life and work. The two lived together for five years and had a daughter, Linn Ullmann, now a noted novelist and journalist. Ullman spent the better part of a decade in Hollywood and on Broadway. She acted in 10 of Bergman’s films and directed two other screenplays (Private Confessions and Faithless), which he wrote after retiring from directing films. These are also two of his most biographic and elegiac films. Ullman has authored two memoirs, Changing and Choices. She hopes to write another.

Already an accomplished Norwegian actress in theater and film, Ullmann had been recommended to Bergman by Andersson, who was a member in Ingmar’s troupe of actors. Legend has it that Bergman ran into the two women sometime on a Stockholm street. When they met, Liv was 25, Bibi, 26 and Ingmar, 46 — a “god” among the mighty film directors of that day, with a distinctive style and themes, as well as his own select troupe of repertory actors. He immediately offered the newcomer a bit role in a film he was going to shoot and in which Bibi was starring. Ullmann accepted, becoming the first foreigner in his Swedish troupe of actors. But shortly thereafter Bergman was hospitalized with a very serious case of influenza. Since the film was interrupted by the filmmaker’s illness, the two actresses took off for a European vacation. -

Celebrating the great Swedish filmmaker’s achievements a century since his birth. Nordstjernan and Ted Olsson are participating in this year-long celebration of the films and achievements of Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s foremost author/director of contemporary cinema.

Celebrating the great Swedish filmmaker’s achievements a century since his birth. Nordstjernan and Ted Olsson are participating in this year-long celebration of the films and achievements of Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s foremost author/director of contemporary cinema. -

New beginnings

During this isolation, which he often craved while composing his films, Bergman conceived an entirely and radically new film on a different topic. By the time he recovered, the two actresses received a notice from the embassy: They were to co-star in Bergman’s new film, the daringly novel Persona, and shooting was to begin in two weeks. They flew back immediately to Sweden.

Thus began Ullmann’s lifelong relationship with Ingmar.

It is interesting that Ullmann’s favorite films, of all she acted in, are Jan Troell’s films, The Emigrants and The New Land, from Vilhelm Moberg’s famous Swedish emigrants saga. Had she never acted in another film, she said she would have felt fulfilled as an actress, grateful for having portrayed this role.

Like Bergman, Troell wrote his own scripts, but unlike Bergman, Troell was also his own director of photography. The Emigrants is based upon Moberg’s first two novels, The Emigrants and Unto A Good Land. The sequel film, The New Land, is based upon Moberg’s last two novels, The Settlers and The Last Letter Home. In both films Ullmann played opposite Max von Sydow, another of Bergman’s staple troupe of actors. While Bergman never forgave his actors (like von Sydow nor Gunnar Bjorstrand) for taking roles in another director’s films, he always forgave Ullmann, attributing this to her Norwegian independence. But Ullmann particularly enjoyed these two films for the role she played of a poor, proud and industrious Swedish immigrant, who lived and loved her life with her husband, contributing to her new country. She had once thought that could be her life, but meeting Bergman changed her life completely and forever, for the better.

Discovering how much these immigrants gave to their new country was unforgettable. She marveled at the couple’s fidelity and fulfilling life under impoverished conditions. After a lifetime of working and living together, they said, “We were the best of friends.” Ironically only after their split were Ullman and Bergman able to confess that same love. -

The young Ingmar Bergman on set.

The young Ingmar Bergman on set. -

Bergman’s actors and crew

Ullmann spoke with great fondness of the troupe that Bergman selected for his films, and of the honor for her to be the first foreigner incorporated onto the team. They were consummate artists, whose skills he trusted completely to bring to life his dramas. They too had great camaraderie and complete trust in one another. Incredibly, over such a long span of time, there was never the slightest jealousy or tension among the troupe and crew. All of Bergman’s team worshipped their director and his stunning creativity. They functioned as a family. And they all delighted in Bergman’s child-like delight in telling jokes with his teammates and to clown with his colleagues. In spirit, Ingmar Bergman was the youngest of them all, Ullmann remembers. But the other important aspect of this teamwork was the collaborative craftsmanship of working together on a film. It took all of them, at their highest art to craft his films. -

Separation and reunion

After Ullmann separated from Bergman, she returned to Norway with their daughter. The press had hounded her throughout their tempestuous relationship and particularly upon their separation, much as was done to Ingrid Bergman after her marriage to Roberto Rosselini, until their prudishness was squashed by public support upon her winning another Oscar.

But soon Ullmann recognized that she had to return to Sweden to earn her living. She dreaded the reception. When her plane landed she could see protest placards, but as she approached she recognized many female actor friends waving “Welcome home, Liv” signs. That night they all camped at Bibi Andersson’s home trading stories of what each had to overcome in their lives. She was welcomed back by her friends and by Bergman into the troupe, for he had recognized from the beginning her amazing integrity as an actor to portray the inner soul of any character. -

Bergman the author

One of the most important contributions of Liv Ullmann’s visit in California was to refocus us upon the significance of Bergman’s writing in all his scripts. She believes that because of his stunning images, people have overlooked the excellence of Bergman the author. She mentioned that people remember the circumstances but do not remember how creative Ingmar’s language is. It is worthwhile to study the scripts.

Curiously, those who are forced to enjoy Bergman films by reading subtitles, which are excerpts of his scripts, may be in a better position to appreciate his authorial superiority than those hearing the language while focusing upon the visual scenes. The miracle was not merely the script, but that in his directing, he transforms the scene into what he had conceived and what he needed the actors to portray. Ullmann says now that Bergman’s gone, cinephiles must study his scripts - not merely his films. She believes we will never see movies with better writing. -

Bergman’s directing style

He wrote an entire script and spent great but lonely periods of creativity trying to make precise his depictions of the human condition in a striking and dramatic way. On the set, he would spend time explaining the drama and blocking the action. He had an uncanny sense of blocking. He thought out each of the angles of the film.

Throughout the entire production he was a keen observer, both to achieve the effects he was aiming for, as well as to notice actors’ gestures or body language that could summarize and symbolize something of the moment or of the theme itself. Again, above all, he trusted his actors and was a marvelous, observant audience for every nuance.

Ullmann so admired Ingmar’s visual sense. The Seventh Seal meant so much to her as a young woman because of its images — so stark, stunning and well-composed, that yes, they can distract from his equally powerful writing.

Bergman placed great trust in all his people: actors and crew chiefs and staff. Every one of those people have contributed to this achievement. He tried to pick the best and relied on them to contribute their talents to this composite art. They added their talents to faithfully represent his concept. The creation (in contrast to the concept), therefore, is a communal art. This is the true reason for the long list of scrolling credits after every film. (When you view your next Bergman film, stay through the credits to appreciate how many people it took to entertain you.)

Bergman and all of his co-workers essentially agreed not to trample on each other’s fantasy. But everyone agreed tacitly, almost as a prerequisite of joining the Bergman troupe’s community, that his script and its vision of the drama, were sacrosanct. Because of this the words of his films are as important, but less studied —until now— than his imagery. This distinction is what makes Bergman’s reputation continue to grow beyond its original, serial reviews of his films and life’s work. -

Bergman’s death

Ullmann had not communicated with Ingmar for some time but was continually thinking of him. One day she sensed that something was wrong and urgently flew to Fårö and went to his house. The neighbor’s housekeeper let her in and informed her that he had been in bed for some days. Ullmann sensed that he was already “on his way out,” sat at his bedside for many hours, communing silently with him. Before she left, without speaking, she responded to this great influence on her career and life, the father of her beloved daughter, and said “because you called” as he had written in Scenes from a Marriage. He died that night.

Reflecting upon his lasting and growing fame after his death, she said, “Artists are forever. They are needed for every generation to teach us who we are and that we are here together and must depend upon one another.” This is his true and lasting message for generations to come, she believes.

Most films content themselves with telling external stories. But Persona, for example goes deep. That is what made this film so revolutionary in its time. It focuses upon the psychological drama of each of us, while he encourages us in Aristotle’s phrase to “Know thyself” or in Shakespeare’s: “To thine own self be true.”

Ullmann mentioned that in turbulent political times such as these, it is worth noting how important our artistic geniuses are to people, reminding them of their fundamental values and the ties of humanity. At the times of the release of his movies many considered Bergman to be dark and fatalistic; instead, Ullmann said, it is the opposite: Perhaps his movies are even more relevant today for showing us how to get beyond darkness. She reminded us that in The Seventh Seal, the knight asks Death for one more day to allow him to do good for someone else to give meaning to his life. Bergman is moral in defining the struggle to be human. -

By Ted Olsson

-

With thanks also to Susan Oxtoby, senior curator of PFA and to Richard Peterson, executive director of CFI, as well as their staffs, for supporting my reporting throughout this year. To bring this celebration to even more people in northern Californians, PFA partners with the California Film Institute of San Rafael, CA. I will have more to say about them and their institutions during the year.

-

-