Movie Review: Cries and Whispers

Love: Daily compassion adds grace to life

-

Celebrating the great Swedish filmmaker’s achievements a century since his birth. Nordstjernan and Ted Olsson are participating in this year-long celebration of the films and achievements of Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s foremost author/director of contemporary cinema.

Celebrating the great Swedish filmmaker’s achievements a century since his birth. Nordstjernan and Ted Olsson are participating in this year-long celebration of the films and achievements of Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s foremost author/director of contemporary cinema. -

-

The plot of Cries and Whispers includes three Swedish sisters and a maid who grew up in the early 20th century. The youngest and oldest sisters have married and moved away but returned because their bedridden middle sister is dying. In the course of one day, with several flashbacks to reveal each sister’s character, Agnes (Harriett Andersson) dies, the estate is settled, and the maid Anna (Kari Sylwan) is dismissed. The eldest sister, Karin (Ingrid Thulin), is out of touch and unfeeling; the youngest, Maria (Liv Ullman), is coquettish with everyone but her cuckolded husband, who after trying to kill himself, was even refused help from his wife.

Bergman once defined this film as a portrait of his mother Karin, the four actresses each playing different aspects of her. We are accustomed to multiple faces being facets of a single character (as in Persona) in Bergman’s biographical and psychological films. Bergman tried to deny this association with his mother, but it is clear the pretty mother (also portrayed by Ullmann), whom all the daughters loved and wanted to be loved by, had a chilling effect upon her daughters — just as Ingmar felt about treatment from his mother. -

In Sweden, the film was promoted with this idyllic scene L-R: Anna (Kari Sylwan); Marie (Liv Ullmann); Agnes (Harriet Andersson); Karin (Ingrid Thulin).”

In Sweden, the film was promoted with this idyllic scene L-R: Anna (Kari Sylwan); Marie (Liv Ullmann); Agnes (Harriet Andersson); Karin (Ingrid Thulin).” -

-

From external to internal: Peace to agony

As the scene opens dawn breaks on a late summer day. The back of a lyre player—as if to accompany this lyric natural panorama—is in blue shade but the sun has begun to stream in the windows of the big house. Various clocks in the home emphasize the passing of time, not only today but in their lives.

The clocks begin to chime and Agnes rises from her bed in great pain. This is a remarkable performance by Andersson, first in the agony of her facial expressions, later in her very labored breathing, or in her scream (the true meaning of the word “rop” in the Swedish title), with Anna’s hands comforting her by clasping the sides of her face.

At first light she gets up to write in her diary about her pain. Reminding herself of how her mother used to retreat to the estate’s garden to relax, Agnes takes out a white rose, appreciating its color—in contrast with her room and living room beyond.

Bergman sets a symbolic palette: By mid-morning the sisters, dressed in their finery (Karin in a severe black suit, Maria in a seductive red dress) are ready to go in to greet Agnes (in her white bedclothes). Anna the maid, up very early and dressed in a simple gray outfit with white apron, has already said her prayers. Despite the pretense of affection, it is apparent the healthy sisters have a strained relationship with their siblings, being much more invested in themselves. This is another one of Bergman’s favorite devices: the mask — the character shows one face to others, assuming that others cannot decipher her true character.

The doctor (Erland Josephson) has been called, his diagnosis is cancer of the womb; but rather than dwell on that, Agnes clutches his hand in hers and brings it toward her face as she tenderly looks upon him. He tells the others their sister’s time is short.

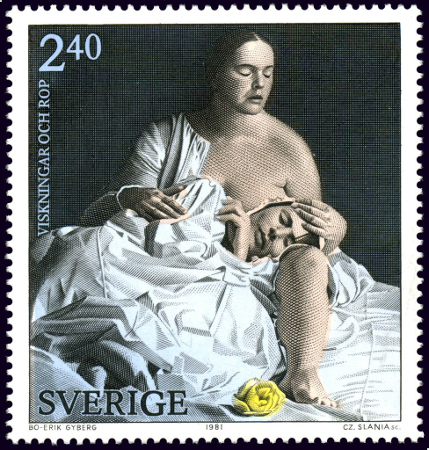

In pain Agnes calls out for her sisters, but they ignore her. It is Anna who comes to comfort her, then climbs into bed and cradles the dying woman so she can sleep. This beatific Pieta scene of Anna and Agnes establishes the dynamic among the four women. -

Sweden celebrates the achievement of Ingmar Bergman, its cultural hero, with this Pieta scene from Cries and Whispers, a tribute to his message of charity for all. Attribution: Swedish postal service

Sweden celebrates the achievement of Ingmar Bergman, its cultural hero, with this Pieta scene from Cries and Whispers, a tribute to his message of charity for all. Attribution: Swedish postal service -

Crimson flashbacks

As the doctor prepares to leave, Maria waits for him. She flirts with him, but he walks out. In a flashback we see she entertained him while her husband was away on business. She mentions the tryst to her husband when he returns, and he attempts suicide by stabbing himself in the abdomen. He calls for help, but Maria abandons him; he survives for later scenes of a failed marriage.

A matching flashback shows the vindictive cruelty of Karin. Sitting across from each other at a long dining table, Karin and her unemotional diplomat husband mince few words while he eats dinner. Karin spills her blood-red wine and shatters the glass after he says he will forego his coffee to have their usual night’s sex later. Retrieving a shard of glass, Karin goes to her dressing room where Anna attends her. While Anna is behind looking at her in the mirror, Karin screams at her not to stare, then slaps her hard. She pleads forgiveness twice, but Anna refuses. After Anna leaves, Karin cuts herself enough to smear blood all over her smiling mouth as her disgusted husband looks at her vindictive taunting grin.

So, the “healthy” sisters are shown to be anything but; rather, they are deceitful, guilty and loveless. The men in the film are sterile and unloved. The only time the siblings show pity for their dying sister is when they briefly wash and change her before returning her to bed to read and entertain her.

Later, as daylight outside the window gradually dims, Agnes glances at the dying Anna beside her, whereupon Anna closes her eyes, clearly indicating her death. -

The sisters comfort their dying sibling while the servant Anna watches in the background.

The sisters comfort their dying sibling while the servant Anna watches in the background. -

Death and God

The next scene shows the church women arranging the body in funereal pose on her bed, then beckoning the priest, sisters and Anna to attend during a brief beside service. Even the priest feels abandoned by God, asking Agnes—who is dead—to plead for forgiveness for each of these people. The priest recognizes the meaning of “Agnes” and “agnus” (“lamb” or “Lamb of God” in Christian theology), for indeed as in earlier historical times, Agnes can be seen as the scapegoat that Abraham finds. In Greek, “Agnes” means “pure” or “holy,” as Anna (from Greek and Hebrew) means “favor,” “grace” and “beautiful.”

Following this comes another remarkable scene in which the remaining sisters make up with each other. We only see them speak endearments to each other; we do not hear their words. Instead, a Bach cello suite in C-minor plays during this temporary harmonious reconciliation. The scene is reminiscent of a flashback in which Agnes, as a terrified little girl, comes at her mother’s beckoning, admitting how frightened she is, and her mother caresses her face with pity.

Often Bergman uses dreams or similar devices to show the psychology of a character. In an earlier day divination was common. Bergman merely updates the technique to cinema, using a “resurrection dream sequence” following Agnes’s death: At the end of the day, Anna seems to hear whispering from Agnes that she is cold, and we assume this resurrection of Agnes is a dream until the dead sister reaches up to clasp Maria’s face. Anna relays the message to Karin but Karin refuses her, for Karin declares that Agnes is dead, and she never liked Agnes anyway. Karin leaves and Anna hears Agnes call for Maria. When Maria returns, she feels Agnes’s dead hands hugging her face. Screaming, she breaks away, saying her husband and children need her. Once again Anna holds the dead sister in a Pieta pose (made so famous that it became a Swedish postage stamp).

After totaling up accounts, the cash-cold Karin divvies up the legacy: they will sell the property for cash and heartlessly dismiss Anna with a pittance, offering her a “keepsake” from Agnes. But Anna says she will take nothing.

The closing scene, however, is Bergman’s benediction, accompanied by Frédéric Chopin’s lively Mazurka No.13 in A-minor. In her own room packing, we see Anna has rescued for herself the most meaningful memento of Agnes: her diary. The trifle that Karin had dismissed as worthless and pitiable is a great treasure to Anna. On the first page, Agnes has written about a time with her youthful and caring sisters, calling it the most perfect day of her life. The film concludes with a final crimson fade-out at one sentence: “Så tystnar viskningarna och ropen” (So the whispers and shouts are silenced).

Technical masterpiece

Cries and Whispers (1972) continues the psychological examination and creative experimentation that Bergman began in The Silence (1963) and in Persona (1966).

The film was panned in Sweden, but it was raved about in the U.S. An early critic said the film was so carefully crafted that it almost doesn’t need the dialogue, since one can understand so much from the images and scenes, particularly the crimson fade-ins and fade-outs on the characters, which reveal so much more about them than their actions on the day of their sister’s death.

In his own comments, Bergman said he and cinematographer Sven Nykvist, who won an Academy Award for this film (which was nominated that year for three other awards: best picture, best director and best screenplay—extraordinary for a foreign film), spent a month of practice shooting to examine every texture, décor and person in the film’s symbolic red color scheme.

Yet another novel aspect of this film was Bergman’s first use of the zoom lens, as recommended by Nykvist. Bergman was not sure about this innovation but Nykvist used the technique so skillfully that Bergman was extremely happy and accepted the new tool. The filming techniques as much as the expressive interpretations given by the actors emphasize how much his films are not merely his inspiration but also the collaboration of his superb team of experts.

While Bergman said he identified red with the soul, it carries cultural symbolism of blood, love and life. So the obsession with red in the Swedish manor is significant; however, so are the identifying flashbacks about each of the key women.

Bergman is a masterful author, and his images illustrate his words but must not distract from them. Like the images themselves, the words and phrases are often repeated at crucial moments in the film. And, sometimes the mastery is in the wordlessness, such as when the two sisters are apparently speaking in endearing terms but we hear only Bach’s harmonious music. -

-

From pity to compassion

Why do Bergman’s films include horrifying scenes, some we do not even want to see? Or others that are painful but we can’t stop watching? Why do we hate some scenes but tolerate others? And why are some characters simply allegorical rather than symbolically complex? We describe some people as “dramatic” when they overemphasize their actions or words, not merely to attract attention to themselves but to make a point memorable. All of these reasons are often used by dramatists to serve their theme.

Such is the case in Cries and Whispers. What can we make of it all: the oppressive atmosphere, the two pairs of women who are so different—spiteful and selfish or tender and compassionate. The natural world outside is warm and beautiful, yet we are horrified at the cruelty inside. We see a physical disease wracking the patient to death and a spiritual one wrenching the other sisters.

The great film critic Roger Ebert once said of this film: “Cries and Whispers is about dying, love, sexual passion, hatred and death—in that order.” That doesn’t sound very satisfying; however, that is the very formula for half the world’s greatest operas. Even the film’s epilogue—silence conquers all—can be said of most of the world’s great tragedies— as Shakespeare concludes Hamlet: “the rest is slence.” -

A symphonic drama

To celebrate Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s cultural hero, the government published a stamp recognizing his achievement. Did they choose a picture of the filmmaker? No. A picture of the spiteful daughter or of the selfish one? No. They chose as an emblem of Bergman’s art the iconic photo of the film, the summation of this tortuous journey: the Pieta moment for Anna and Agnes, the picture of charity or human kindness and compassion.

It is unfortunate that so many viewers do not know how to see Bergman films or how to comprehend them. They see only abhorrent scenes and focus upon repellant images, rather than remember the essence of the film by Bergman and his collaborating artists. In the end, seeing the ruin of the lives of the three sisters and the composure of the survivor, we can only pity our human condition for those who are unable to witness daily the miracle of the mundane and the kindness of others. Instead we witness a callous plague daily in the news of today.

We are left to marvel at the concept of the film and the actors—each playing exquisitely their allegorical roles as instruments in Bergman’s symphonic drama (as he liked to think of this masterpiece), but the marvel of this team is that they make this imaginative act live for us and resonate within us long after we leave the theater. -

By Ted Olsson

-

-