Bergman's radical Persona

Who are you? How do you know? questions the psychological drama, one of Ingmar Bergman's masterpieces.

-

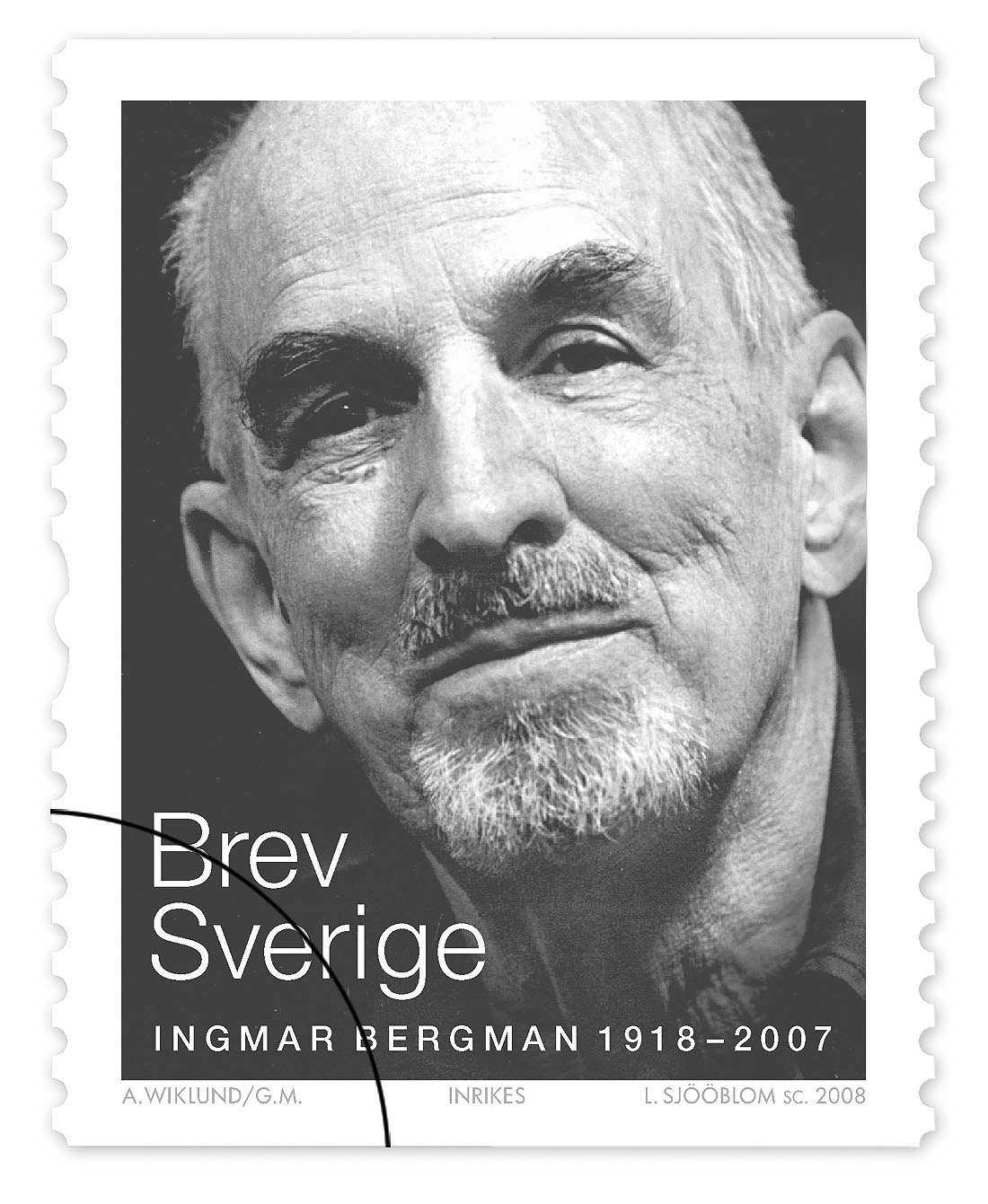

More Bergman 100 celebrations with screenings at the Scandinavian Cultural Center in West Newton MA. “I said that Persona saved my life—that is no exaggeration,” remarked Bergman. “If I had not found the strength to make the film, I would probably have been all washed up. One significant point: For the first time I did not care in the least whether the result would be a commercial success.” - The 2008 stamp from Posten features Ingmar Bergman.

More Bergman 100 celebrations with screenings at the Scandinavian Cultural Center in West Newton MA. “I said that Persona saved my life—that is no exaggeration,” remarked Bergman. “If I had not found the strength to make the film, I would probably have been all washed up. One significant point: For the first time I did not care in the least whether the result would be a commercial success.” - The 2008 stamp from Posten features Ingmar Bergman. -

-

Ingmar Bergman’s film Persona (1966) is one of his supreme masterpieces. Biographer and film critic Peter Cowie noted (rather like Newton’s universal law of physics), for every opinion (action), there is an equal and opposite reaction. Certainly what is distinctive in all critiques are the unique montages that distinguish this film. These are carefully explained frame-by-frame and as a sequence by Cowie in his introduction to the recent Criterion Collection of Bergman films in time for this centennial, and by Bruce Kawin’s Mindscreen book.

It is useful to remember the circumstances of the film's inception. Bergman had signed on Bibi Andersson to star in a film that he was intending to make, when he met Liv Ullman and offered her a bit part in that film. Shortly after, he became ill and was hospitalized; during his convalescence, Bergman had an epiphany. He tossed out the original script and began conceptualizing a new one starring both Bibi and Liv. He did this while still in the hospital, with all the ideas that brought him. He completed the screenplay and started shooting Persona two weeks later. -

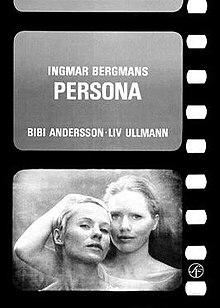

In the publicity for this film, especially in the promotional poster, Bergman required the photo of the two characters be framed by film sprocket holes on the right side of the picture, emphasizing the distinction between reality and imagination. Photo ingmarbergman.se

In the publicity for this film, especially in the promotional poster, Bergman required the photo of the two characters be framed by film sprocket holes on the right side of the picture, emphasizing the distinction between reality and imagination. Photo ingmarbergman.se -

-

Montages

Persona opens with an introductory montage that gives an eye-blinking summary of film history, themes and technology, including the projection of images. This prologue begins with arcing rods, which originally illuminated projectors, heating up and producing the light to project the film’s images like “Fiat Lux.”

In this first part there are many “eyeblink images,” and it appears the film derails and seems to burn up. This was so significant in the original showings of the film that the reels were shipped to theaters with warning labels notifying projectionists to disregard the effect of the projector burning the film. That itself is another key to this film: distinguishing between reality and artifice.

The initial montage symbolically reveals that Bergman was planning another typical movie. Then he jettisoned that for an entirely new presentation, one allowing him to closely examine the psychology of his two main characters, who look similar. He even includes a shot from a hospital morgue where a supposedly dead boy wakes up on a gurney, trying to make sense of his whereabouts and wipes his hand across the lens/screen as he tries to make out a blurred face, which is the merged superimposition of Andersson and Ullmann’s faces, one of several iconic photos from this film.

All that was the creativity of the director in the editing room. When Andersson and Ullmann were each shown this photo, their first reactions were to pity how strange the other looked, without at first appreciating the symbolic overlay. Nykvist and Bergman purposely combined the less attractive half of each actress’s face.

There has been much discussion of this initial montage. Midway through the film, after the two characters recognize each other as opponents, the film symbolically again splits and burns, indicating the severity of their split and the reformation of this pair. And at the end, among the shots in the final montage, is a photo of Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist behind the camera shooting this film. Again, we are reminded of the distinction between fiction and fact, and that fiction may creatively mirror or rearrange the meanings behind a fact, making its significance clearer and more compelling.

This novel technique marks a new beginning for Bergman and his company in telling stories through film. Bergman is clearly making the filming of this story itself obvious (like DuChamps’ 1917 Fountain urinal). It is not “existential reality” as we experience it, it is a narrator’s reality created for us to better appreciate a message from a new perspective — an “artificial reality” created by art and craft. -

Elisabet photographs the audience; we're complicit in this story.

Elisabet photographs the audience; we're complicit in this story. -

The story

Persona follows Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann), an accomplished actress who stars in a play but stops mid-dialogue and goes completely silent. After several days of silence she is hospitalized, and the supervising doctor makes two decisions: She assigns her young nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson) to tend to Elisabet and later decides the two women may stay at her isolated beachfront home where the solitude may help Elisabet’s recovery.

A fateful moment not many critics refer to is when the doctor reveals Elisabet’s diagnosis: “I understand why you don't speak, why you don't move, why you've created a part for yourself out of apathy. I understand. I admire. You should go on with this part until it is played out, until it loses interest for you. Then you can leave it, just as you've left your other parts one by one.”

As we experience the film we remember this professional explanation. We see that Elisabet is not merely willful (rather than psychotic) — reinforced by her study of Alma as revealed in an open letter — but also that this is a phase that at any moment Elisabet can end in order to fashion another role for herself. What is unpredictable (and likely not even considered by the character) is how her experiences during this period of silence will affect her next phase or role and the rest of her life.

The main part of the story concerns the women’s time at the beach house. Elisabet is silent but pleasant; Alma is talkative and caring. They seem to form a bond of friendship, but the silence begins to wear on Alma. When she discovers Elisabet has betrayed her confidence, the roles reverse and Alma sets aside her caregiving duties and pursues Elisabet to break her silence and breakthrough her “persona.” -

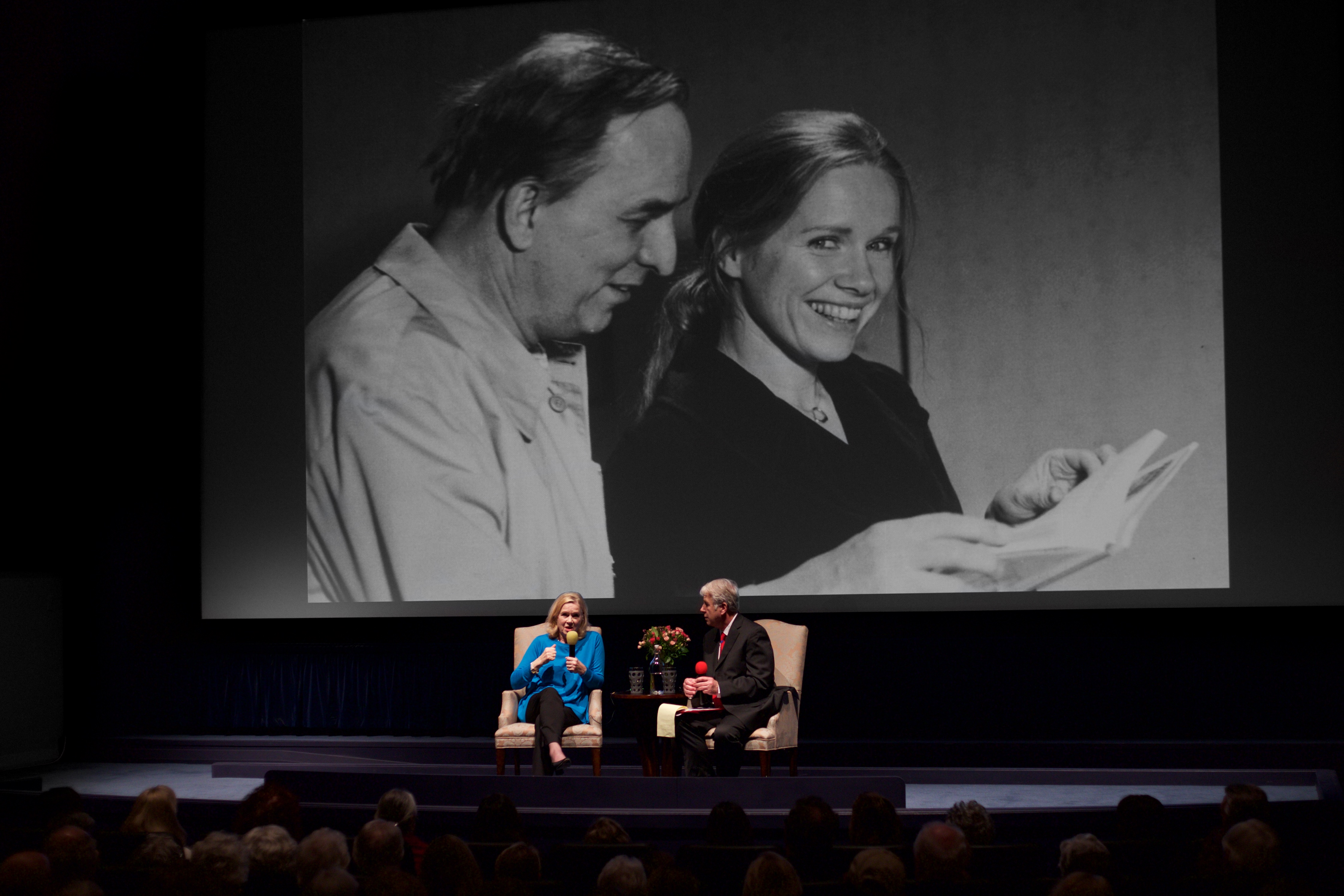

Liv Ullman was interviewed on stage at CFI by Richard Peterson following viewing of Persona, with photo of Ingmar and Liv on screen. Photo: Tommy Lau

Liv Ullman was interviewed on stage at CFI by Richard Peterson following viewing of Persona, with photo of Ingmar and Liv on screen. Photo: Tommy Lau -

Passion

The women’s relationship becomes more passionate after each character exposes her vulnerabilities to the other. The first half of the film is essentially a time of bliss and companionship. Elisabet also receives a letter from her estranged husband who wishes to work on repairing their marriage. Alma offers to read the letter to her, and while this is necessary for us to learn background on Elisabet, it seems that so secretive a woman would not permit this view of another aspect of her life. The letter includes a photo of their son. When Alma hands it to Elisabet, she looks at the photo and tears it in half, keeping the pieces. This is shocking to Alma — and the viewer.

Alma confides in Elisabet, confessing an erotic experience in her life, claiming she never enjoyed such sex before or since, which also resulted in an abortion she kept a secret from her fiancé. As time goes on we see the effect Elisabet is having on Alma. She imagines Elisabet caringly communicating to her softly, and Bergman, like Alma herself, does not distinguish between dreaming and wakened reality— to Alma all is reality. In one scene we see Elisabet go into Alma’s bedroom, stand behind her and turn Alma’s head in profile beside her own. This poster shot, one of several iconic images of this film, indicates how similar these two women are, after which they nuzzle their necks in affection. Later both women are in bed as Alma breaks into tears saying that it is so difficult to distinguish what is real and what to do.

The scene the next morning is equally striking and significant. Alma is off in the distance while Elisabet enters into full view in the foreground—and focusing on the audience, she snaps our photo. Now the audience is equally and fully complicit in deciphering what is real.

Soon Alma rejoins Elisabet and the nurse asks the patient two pregnant questions: Did you speak to me last night (at the table)? Elisabet shakes her head and mouths "no" with a look of curiosity about the question; next Alma asks, “Did you visit me in my bedroom last night?”

Later, the two go into town and Alma offers to mail a letter for Elisabet (left unsealed by Elisabet—on purpose?). Her curiosity leads her to read it and she learns that Elisabet has lied to her. Alma feels betrayed and screams at Elisabet. Later Alma shatters a wine glass in the garden but saves a shard of glass and places it where Elisabet will step on it. She even watches Elisabet come and go several times without getting hurt. But when the shard finally pierces Elisabet’s foot and she cries out, she looks at Alma and in that exchange the film “breaks” into the middle montage where the film is seen to catch on fire. Now the tables are turned.

In the second half of the film, Alma hears someone outside. She finds Mr. Vogler, and he confuses Alma for his wife Elisabet, whom he has come to gain reconciliation with. Even as Alma protests that she is not Elisabet, and Elisabet gets behind Alma (rather as in their nighttime dream sequence) and caresses the man’s face with Alma’s hand, Mr. Vogler takes Alma to bed. The audience interprets this as another of Alma’s dreams or visions of alternative reality. This is but another clue from Bergman to help us understand the two characters as alternating versions of a single person.

But the most astounding scene is of dueling monologues. At first the camera is focused upon Elisabet as Alma explains how Elisabet became pregnant, tried to have an abortion, and finally after the baby’s birth wished he was dead because a baby threatened her acting career. She abandoned him, yet the boy loved his mother.

During this accurate depiction, Elisabet tries to be stoic, to deny all, but reacts to the charges. What makes the duel so striking is that Bergman repeats the entire monologue this time focused upon Alma. Obviously, Alma could not intuit, let alone know, all these facts, unless they are one and the same person.

In the end, before Alma abandons her charge, Alma repeats to Elisabet: “I’m not like you. I don’t feel like you. I’m Sister Alma, I’m just here to help you. I’m not Elisabet Vogler. You are Elisabet Vogler.”

Before the montage that concludes the film, we see Alma pack up and board a bus that will let her escape from this hell. She returns to the communal world of the living, where people exist and survive by speaking and sharing their daily experiences. Presumably she returns to life with Karl Henrik and they will have children. Presumably the experience has taught her to live and communicate with others, as humans do, which makes existence bearable and even enjoyable. -

Bergman100 Team: Richard Peterson (CFI), Susan Oxtoby (PFA), Liv Ullman, Consul General of Sweden Barbro Osher, Dr. Donald Saunders (Liv’s husband). Photo: Tommy Lau

Bergman100 Team: Richard Peterson (CFI), Susan Oxtoby (PFA), Liv Ullman, Consul General of Sweden Barbro Osher, Dr. Donald Saunders (Liv’s husband). Photo: Tommy Lau -

Pairings

Bergman typically uses pairings of words or images to reinforce his meanings. One of the earliest of these is the horror and revulsion in her silence that Elisabet experiences in seeing two visual images. Isolated in her hospital room, Elisabet is watching television and notices a news clip of a Vietnamese Buddhist monk’s self-immolation in protest of the American war in Vietnam. While horrified by the pain suffered in silence, with great discipline unto death by the burning monk, Elisabet shrinks into a corner of the room, frightened, with mouth agape. We imagine she is stunned by the spectacle and pities the circumstances that brought the monk to make this gesture, and we also suppose Elisabet must measure her own act of defiance compared with this one.

The matching image, during her stay at the beach house, is when Elisabet comes across another famous photo of a boy and family with raised hands being herded by a shouting mob, as the Germans round up Jews during the Holocaust, which similarly will likely end in the execution of these fellow humans. Bergman has selected these two photos of different wars to show not merely the innocent victims, but also the fury and support of their neighbors which allows this horror.

There are other pairings of images, emphasizing Alma’s erotic narration, her hope for children and a normal family, Elisabet’s pregnancy and motherhood, and the silent “persona” of Elisabeth and the talkative “soul” of Alma—all reasons for considering two halves of ourselves, seen from opposite perspectives. -

Celebrating the great Swedish filmmaker’s achievements a century since his birth. Nordstjernan and Ted Olsson are participating in this year-long celebration of the films and achievements of Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s foremost author/director of contemporary cinema.

Celebrating the great Swedish filmmaker’s achievements a century since his birth. Nordstjernan and Ted Olsson are participating in this year-long celebration of the films and achievements of Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s foremost author/director of contemporary cinema. -

Confronting a classic

Adding up all of these elements—the story and filming, the superb acting (imagine Liv Ullmann making her initial appearance starring in a Bergman film with only three words!) and the intense and prolonged close-up shots, the montages and symbolic composite photo, the interplay between external reality and perceptions—what can we make of this film?

It is important that we put the film in its historic context. There are other famous examples of multiple, simultaneous perspectives (Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961); Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957)), requiring the viewer to make sense of conflicting views and confronting ambiguity. One distinction is that such art films require the viewer to accept it as part of one’s education. Some movies are mere entertainment, and other classics may be meaningful and superbly filmed without requiring such introspection. Some may be difficult to understand and bear repeated viewing, each time providing more enlightenment, if merely to admit that it is a classic. For Alma, and for us, this experience—of the story and of the film—is transformative. We do not live alone. And only as we care for others, do we live. Persona is one of Bergman’s great masterpieces. -

Ted Olsson interviewed Liv Ullmann to appreciate her skills and her perspective on the multitalented Ingmar Bergman. Photo: Tommy Lau

Ted Olsson interviewed Liv Ullmann to appreciate her skills and her perspective on the multitalented Ingmar Bergman. Photo: Tommy Lau -

By Ted Olsson

-

-