Shaping magnetism: Bjorn Kjellstrom and orienteering

Outdoor Adventures, navigating the Nordic Way opens this weekend at the American Swedish Historical Museum

-

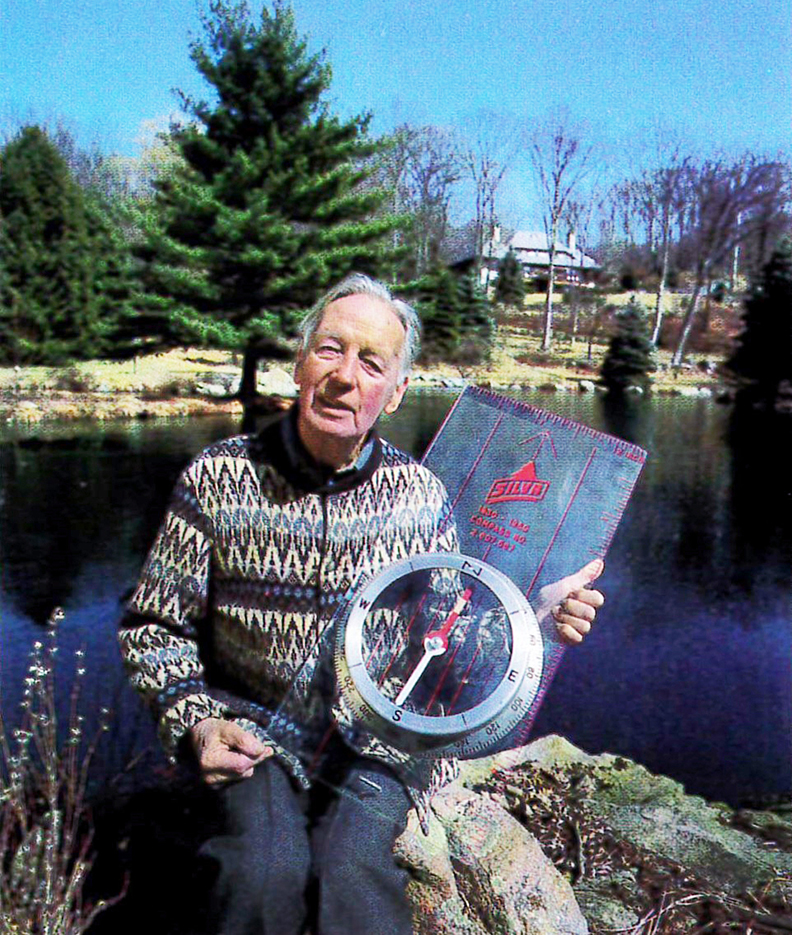

Björn Kjellström and Chris Cassone pose with a large-scale version of Björn’s early orienteering compass.

Björn Kjellström and Chris Cassone pose with a large-scale version of Björn’s early orienteering compass. -

-

When Americans think of orienteering, one of two images likely come to mind. First, that of brightly-clad men and women sprinting through dark forests while searching for even brighter orange checkpoints. They might also think of young scouts consulting their compasses, yearning for a merit badge as much as the end of the course. Both, of course, are accurate. Orienteering, a sport that mirrors the Scandinavian spirit:

Orienteering: It's all about finding your way -

Meet “Mr. Orienteering,” Björn Kjellström, who started the Silva Compass Company in the U.S. when he arrived in 1946. He lived most of his life at Pound Ridge, NY, but died in Sweden in 1995 at age 84.

Meet “Mr. Orienteering,” Björn Kjellström, who started the Silva Compass Company in the U.S. when he arrived in 1946. He lived most of his life at Pound Ridge, NY, but died in Sweden in 1995 at age 84. -

-

Orienteering is an international sport requiring use of map and compass to navigate an outdoor course. It is also a popular merit badge for both Boy- and Girl Scouts. While variations of the sport might involve skis, bicycles or a wheelchair, orienteering’s archetypical competitions are on foot and scored so the orienteer with the fastest time wins.

What people do not often think of, however, are peaceful walks through the forest or quiet outdoor adventures. To Björn Kjellström, orienteering was a way for people to re-connect with nature and appreciate its beauty and mysterious forces. Kjellström embodied this appreciation in his motto: “Magnetism has shaped my life.” -

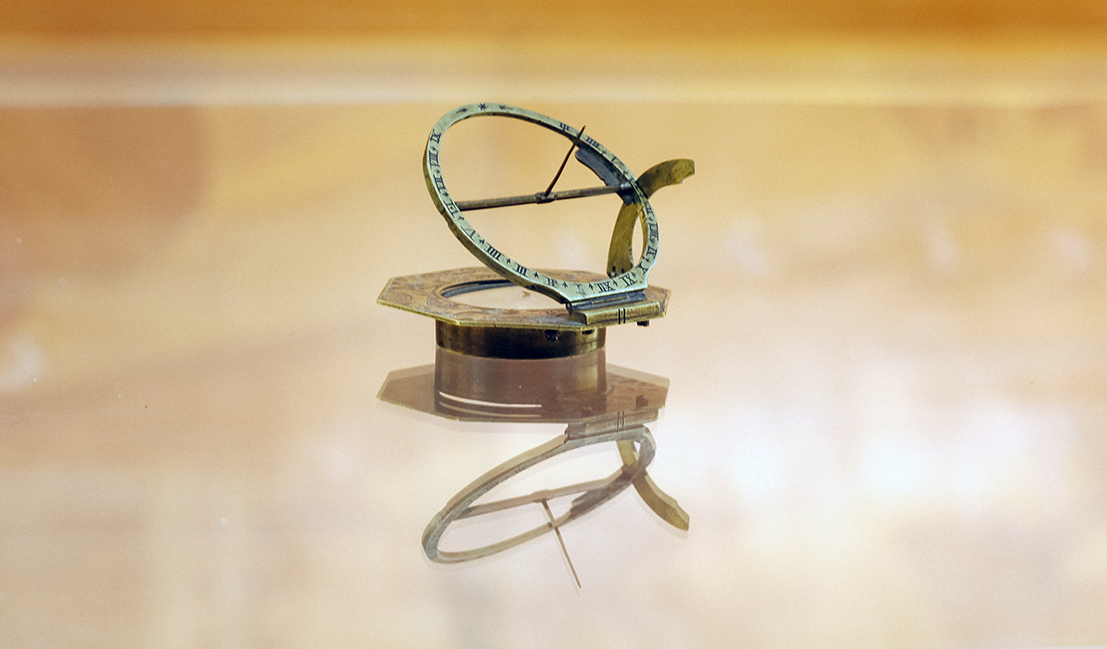

On display at American Swedish Historical Museum and part of Kjellström’s impressive collection is this Austrian combination sundial and compass, likely dating to c. 1770.

On display at American Swedish Historical Museum and part of Kjellström’s impressive collection is this Austrian combination sundial and compass, likely dating to c. 1770. -

The modern compass

As the co-inventor of the modern compass and the man most responsible for the global spread of orienteering, Björn Kjellström has shaped our appreciation for magnetism as much as it shaped him.

Long before Kjellström’s first orienteering competition in 1928, the sport had developed from Swedish military exercises in the late 1800s. These practices taught soldiers how to navigate terrain only with their map and compass, which at the time was often mounted into a protective wood box. The first orienteering competitions were held in May 1893 around the Stockholm city garrison, and by 1897 civilian competitions were taking place near Oslo. While military navigation was the sport’s natural origin, its exposure among civilian outdoorsmen was enabled by Sweden and Norway’s industrialization, railroads and the necessitation of land surveying. Such surveys, in conjunction with printing technology such as lithography and subsequent tourist maps, encouraged the widespread availability of maps for public use.

Despite orienteering’s early popularity among Sweden and its Nordic neighbors, the sport’s global spread was halted by the technical limitations of the compass. While early orienteers used protractors together with their compasses to navigate, the difficulty of using these two tools in the field alongside a map meant that precise navigation was challenging. Additionally, the magnetic needles within these “dry” (not liquid-filled) compasses could take about 30 seconds to stabilize. In a sport where a few degrees might take one miles off-course, these limitations frustrated attempts to popularize the early sport amongst amateurs.

The solution came through collaboration between the three Kjellström brothers—Björn, Arvid and Alvar—and a local inventor named Gunnar Tillander. Orienteering was hardly new to the Kjellströms—they had competed on skis during their childhoods and had recently started a business selling used compasses and ski equipment. But their breakthrough came in 1928 when Tillander approached the brothers with his prototype for a compass incorporating both protractor and compass into a single instrument. The design, familiar to us today, mounted a rotating compass onto a clear plastic baseplate that allowed for accurate navigation when placed over a map. Tillander’s invention essentially removed redundant equipment from the orienteer’s toolkit while making navigation even more precise.

One Kjellström brother, Björn, supplemented Tillander’s compass with his own invention: a liquid damping chamber for the magnetic needle. By submerging the magnetic needle in a clear liquid (often a clear oil or ethyl alcohol), the time needed for it to stabilize was reduced from about 30 seconds to only four. The liquid also formed a buffer against exterior shocks and vibrations—necessary to orienteers in the field. Tillander and Kjellström’s innovations were vital in improving the accuracy of field compasses, reducing orienteering’s complexity, and increasing the sport’s competitive viability. -

In Kjellström’s impressive collection is this Austrian combination sundial and compass, likely dating to c. 1770.

In Kjellström’s impressive collection is this Austrian combination sundial and compass, likely dating to c. 1770. -

Putting it on the world map

The Kjellström brothers and Gunnar Tillander formed their company, Silva, in 1932. Silva was instrumental in further popularizing orienteering in Sweden, and by 1934, upwards of a quarter million Swedes were active in the sport. Beyond Sweden’s borders, it had become popular among the Nordic countries, playing a key role for Finland’s army as it resisted the Soviet Union during the Winter War and helping Norwegian resistance fighters combat Nazi occupiers after 1940. According to his children, Björn Kjellström himself volunteered with the Finnish Army, and later with his first wife, a Norwegian, provided a safe house for Norwegian refugees. After the war, he immigrated to the United States.

During his first year in the U.S., Kjellström organized orienteering events for the Boy Scouts in Indiana. While America’s first orienteering competitions had already been organized by Finnish army officer Piltti Heiskanen in 1941 at Dartmouth College (which the students called Tiedust, an anglicization of the Finnish name for orienteering, Tiedustelujuoksue), the sport had not yet caught on in America. Kjellström’s promotion of the sport culminated in his 1955 book, Be Expert with Map and Compass. This guide to orienteering has sold over 500,000 copies and has remained in continuous print since first being published.

Kjellström promoted and organized orienteering events in America through the late-1940s and 1950s, but it was not until the 1960s that orienteering began to find its niche in the United States. This decade saw the birth of the Delaware Valley Orienteering Foundation, today the largest orienteering club in America, and the popularization of orienteering with the Marine Corps and West Point. In 1971, Kjellström co-founded the United States Orienteering Foundation (USOF). As the USOF’s long-time co-president and president emeritus, he had become the figure most widely associated with orienteering throughout North America. Today's Silva of Sweden: After twenty years absence, the original Silva compass is back on U.S. store shelves. -

Photo: Fredrik Broman/Imagebanksweden.se

Photo: Fredrik Broman/Imagebanksweden.se -

A Swede's love of nature

Despite being a champion orienteer, skier and event organizer, Kjellström’s love for the sport drew from its closeness to the natural world and quiet appreciation for nature. As stated on his business card, magnetism captivated Kjellström. At his home in Pound Ridge, New York, Kjellström developed this fascination through his enormous collection of historical texts on magnetism and antique compasses from around the world. His collection included 17th century Jesuit texts on magnetism’s application in theology, ancient Chinese compasses, and dozens of 18th century pocket compasses from France, Austria and Portugal.

Later in his life, Kjellström even took pilgrimages to the magnetic North Pole. He delighted in the unlimited freedom enabled by mastering map and compass, and often reminded his friends: “Magnetic waves run from pole to pole, coursing right through our bodies, 24 hours a day. And ... they are free!" His friend and student Christopher Cassone says, “Magnetism was always on his lips.”

Björn Kjellström’s love for the natural forces did not end at magnetism. His daughter Carina notes that her father loved the slower aspects of orienteering as much as its fast-paced competitions. Around his home in upstate New York, Kjellström’s six-foot-three frame was a daily sight on the trails he developed in the 4,700-acre Ward Pound Ridge Reservation. Even through his last years, Carina recalls her father's love for outdoor exploration by orienteering. Although he was slowed by age, ski poles allowed him to continue appreciating nature’s beauty through his last years. And today, though Björn Kjellström is no longer with us, his legacy endures in the empowerment and freedom learned when harnessing magnetism with map and compass. -

By Trevor Brandt

-

To learn more about Björn Kjellström’s life and his extensive collection of compasses, visit the American Swedish Historical Museum’s special exhibit: Outdoor Adventures: Navigating the Nordic Way. This exhibition is on view April 6 to September 22, 2019. www.americanswedish.org

-

-