Exporting the Swedish dad

Sweden has played a decisive role in the changed views of equality between the sexes in many countries.

-

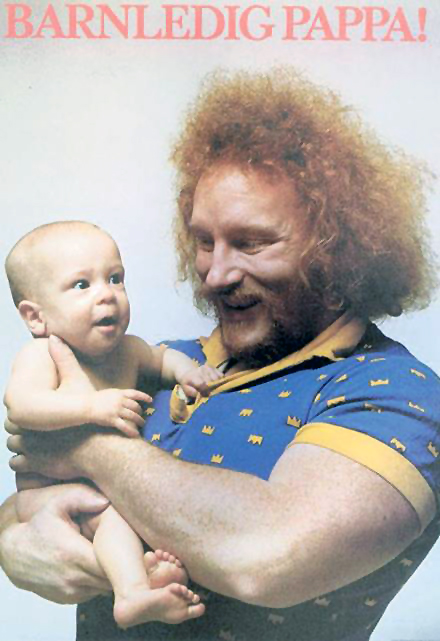

The Swedish dad—now on export to Russia (among other countries). Above: Weightlifter Lennart “Hoa-Hoa” Dahlgren in a legendary ad for paternity leave from 1978.

The Swedish dad—now on export to Russia (among other countries). Above: Weightlifter Lennart “Hoa-Hoa” Dahlgren in a legendary ad for paternity leave from 1978. -

-

Sweden has played a decisive role in the changed views of equality between the sexes in many countries. Take the Swedish idea to get men more involved with their children, for instance, which began in the early 2000s through a project financed by Sida (Styrelsen för Internationellt Utvecklingssamarbete or The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency), in eastern Europe. Eventually the so-called “pappagruppsmetoden” (the dad-group method) began popping up in countries like Ukraine, Russia and Belarus.

One dad in St. Petersburg, Russia is one of them. Though Sergei Zacharov was reluctant at first, when he and his wife Anna were pregnant with their daughter Maria, now 3, he quickly became engrossed in the idea of getting more engaged in his child. “I went to a meeting (at a dad’s group) and felt almost immediately that I liked it. It was the first time I could raise the questions I had with other expecting fathers, questions about the pregnancy, and especially the delivery,” he says in an interview with DN.se.

Zacharov engaged in the organization Northern Way, and is now leading a dad’s group at a maternity center in St. Petersburg, where he meets with and talks to new fathers and fathers-to-be. “The first time, you feel insecure about what role to play, and how to support the woman, how pregnancy works and how you can best assist at the delivery. Fathers-to-be also want to discuss what to buy, and how to equip their homes.” -

-

-

More involvement, more prepared

Fathers meeting like this is something new in many parts of the world, including Russia. For many it is still unthinkable to take a day off work to meet other fathers. “Unfortunately there are still many who are reluctant and don’t understand,” says Zacharov. “But one meeting can often change that.” The men say that as a result of meeting other men who are about to become fathers, they strengthen their relationship with their wives or partners. They become more engaged and involved in the pregnancy and the delivery. Even their women report that the men seem to become more ready to take on responsibility. Zacharov says it’s important the women stay away from these meetings, however. “Every time I’ve tried mixing groups, men seem to take the backseat. They become less actively involved, and there’s nothing strange about that, since it’s the woman who is in focus during a pregnancy.”

These early trials have been highlighted in Russian media, just the way they were once highlighted in Swedish press during the 1970s and 1980s. As late as the 1990s there were Swedish psychologists warning expectant fathers against being involved at the delivery, saying the risks that they would faint and that their sex life would be damaged were great. Because of this, Zacharov feels it’s important to move ahead slowly. He meets five times with a group of eight fathers, and when a group is ready, he takes on the next. The aim is to plow new ground and create a climate that will eventually create a demand. “What’s important is that we create something lasting. If we move ahead too quickly there’s a risk it may backfire. Russian society is not quite ready for this to become a mass movement,” he says. But the effects of these types of groups can already be seen: A change in Russian law now makes it possible for all men to participate at the delivery, legally and free of charge. Prior to this, only a few hospitals offered this service, and you had to pay for it.

Zacharov says he and his wife share the responsibility of their daughter equally. The last time their daughter was ill, it was Zacharov who took time off from work to stay home with her. Many of the men who come to the groups say they want to take more part in what’s going on at home, so their wives can go back to work. And when his own daughter falls and hurts herself she runs to whatever parent happens to be closest, not necessarily her mother. “When I am home with her, she asks for her mother,” Zacharov says. “But Anna says that when she is at home with her, she asks for me.” -

-