Along the shores of Lake Vattern, part 1

A two-part account of a journey through Ostergotland in south central Sweden.

-

Karin and Frederick Eklund in front of Göta Hotell.

Karin and Frederick Eklund in front of Göta Hotell. -

-

Travel writer and photojournalist Bo Zaunders often reaches back in history to shape the itineraries of his expeditions. This two-part account of a journey through Ostergotland in south central Sweden is no exception. Part 1: The eastern shores of Lake Vättern, From Vadstena to Visingsö.

-

Göta Hotel’s Karin Eklund plating poached salmon/ Vätternröding with new potatoes.

Göta Hotel’s Karin Eklund plating poached salmon/ Vätternröding with new potatoes. -

-

Chivalry did not begin with Sir Walter Raleigh laying down his valuable cloak in the muddy ground to prevent Queen Elisabeth I from dirtying her feet.

In Sweden long before that, a giant named Vist, making sure his wife had something to step on as she crossed Lake Vättern, threw a tuft of grass into the lake, thus creating the island of Visingsö.

Moving from gallantry and legend to medieval history, this sliver of an island, 7½ miles long and less than 2 miles wide, was once a hotbed for Swedish royalty with some half a dozen kings using it as their home back in the 12th and 13th centuries. -

Övralid, Verner von Heidenstam’s last home by Lake Vättern.

Övralid, Verner von Heidenstam’s last home by Lake Vättern. -

Now, while approaching the island by ferry, Visingsborg, an old castle ruin, is one of the first things that catches the eye. Dating back to the mid-1500s, it is something of a newcomer, built to replace Näs, the first royal castle of Sweden, which burned to the ground in 1318.

History permeates not just the island but the entire eastern shore of Lake Vättern, a stretch along which my wife Roxie and I traveled for a few days this past summer. -

The renowned author’s work area with desks and chairs arranged to avoid distraction by the view.

The renowned author’s work area with desks and chairs arranged to avoid distraction by the view. -

The journey begins

Visingsö, which lies at the southern end of the lake, was our final stopping point on a journey that began in Linköping, the capital of Östergötland County. From there, in a rented car, we headed north-northwest. Our first stop: Göta Hotell in Borensberg, a large red, wood building with white trim, familiar to anyone who ever cruised the Göta Canal, Sweden’s famous 19th century waterway.

Arriving at lunchtime, we met with Karin and Frederick Eklund, the couple who owns the hotel and its restaurant. There, in a dining room overlooking the canal, I indulged in — what else — Vatternröding, the delectable char for which the lake is famous. Roxie, meanwhile, ate poached salmon, expertly plated by Karin and served with the kind of scrumptious new potatoes in which, during the summer, the whole country takes well-deserved pride. -

The bed room was another story entirely of course.

The bed room was another story entirely of course. -

Verner von Heidenstam's Övralid

In good spirits, we continued toward Vadstena, making a stop at Övralid, Verner von Heidenstam’s last home.

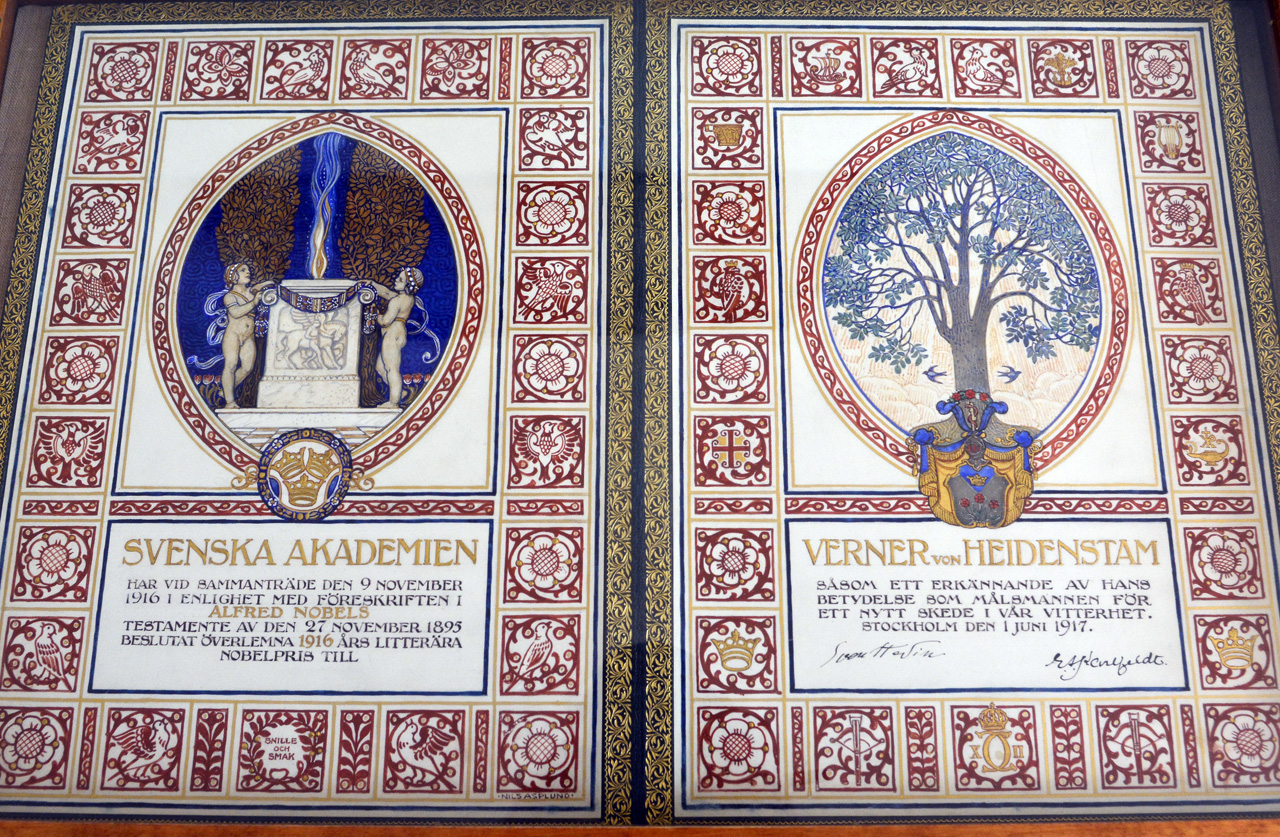

So who was Verner von Heidenstam? Had the question been asked a century ago it may have raised an eyebrow. Then at the top of his game, Heidenstam was quite a celebrity and just about the most famous and respected poet and writer in all of Sweden. A leading figure among the literary romanticists of the 1890s, he later became a member of the Swedish Academy and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1916. To Swedes from earlier generations, his most beloved work may have been Karolinerna (The Charles Men), a series of historical portraits of King Charles XII and his cavaliers, a narrative steeped in unabashed patriotism. -

Verner von Heidenstam was the 1916 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his significance as the leading representative of a new era in our literature.”

Verner von Heidenstam was the 1916 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his significance as the leading representative of a new era in our literature.” -

A blueblood through and through, and rather overbearing at times (he was involved at one point in a highly publicized debate in which he and his old patron August Strindberg fought each other viciously), Heidenstam also showed a human side. Which brings us to his rambunctious wedding on the small Baltic island of Blå Jungfrun in the summer of 1896. Apparently it was a Dionysian feast without compare, an orgy of nudity and abandon. In faded photographs you see him and his guests, prominent artists and writers such as Albert Engström and Gustav Fröding, dressed in togas, skinny dipping or romping through the woods with nothing but leaves to cover themselves.

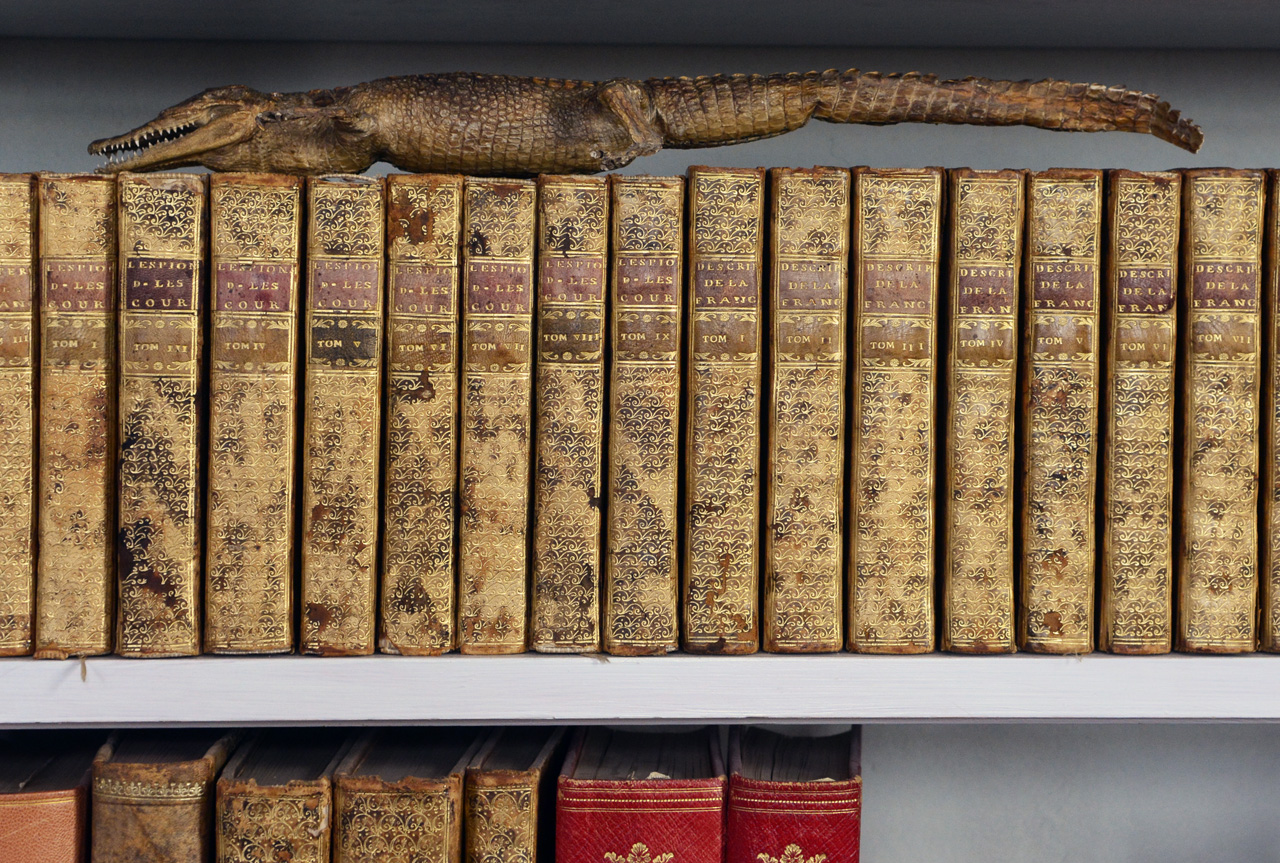

In 1925, Heidenstam moved to Övralid, the manor house he designed and had built on a hillside next to Vättern. It’s now a museum, kept the way it was at the time of his death in 1940. There we met with manager Per-Gunnar Andersson, who enthusiastically guided us from room to room, displaying an inexhaustible knowledge of everything connected to the great “national poet.” The library, his favorite room, had some 3,000 books sorted by color. Those with golden backs were placed to reflect the sun at sunset. There were also blue, red and green spines, the latter to replicate the forest outside one of the windows.

In the study, desk and chairs were arranged so the beautiful lake view would not distract him while working. On the other hand, he loved watching it while shaving, as evidenced by a large shaving mirror right in the middle of his bedroom. Another bedroom was for Kate Bang, the woman he lived with at the time, and others were for dear friends and frequent visitors, such as Prince Eugene and explorer Sven Hedin. In the kitchen stood the first electric model of an Electrolux 1934 refrigerator, still in good working order. -

Heidenstam was a man of many interests.

Heidenstam was a man of many interests. -

As we passed through the main hallway I took note of an imposing statue of Heidenstam’s mythological hero Folke Filbyter, sculpted by Carl Milles, yet another close friend. In the library, I caught sight of a worn out rapier, used in the wars that raged back in the early 1700s. Per-Gunnar’s eyes shone with excitement as he picked it up. “On his 70th birthday,” he said, “Heidenstam was given a lot a fancy gifts, but this, by far, was his favorite.”

Looking toward the lake, we could see his tomb and final resting place. “He designed it himself,” Per-Gunnar said, and told us of a meeting he had a long time ago with a man who, as a teenager, helped build it. As work on his tomb progressed, Heidenstam would often show up for inspections. “Make sure I get plenty of space,” he told the workmen, “as I’m suffering from claustrophobia. And also, as you can see, I’m quite tall, 193 cm (6 feet 3 inches).” -

Övralid’s Per-Gunnar Andersson with Heidenstam’s18th century rapier.

Övralid’s Per-Gunnar Andersson with Heidenstam’s18th century rapier. -

Before we left Övralid, Per-Gunnar presented me with a bag full of various paraphernalia. Printed on the bag was a photo of Heidenstam, sitting on the terrace, gazing at his beloved lake — always that aristocratic profile, shown in practically every picture of him.

-

Övralid library.

Övralid library. -

Vadstena

Driving south, we arrived in Vadstena, a medieval town best known for its connection to Sancta Birgitta (Saint Bridget), its Abbey Church and Renaissance castle. Here for an overnight stay and dinner, we checked in at the Vadstena Klosterhotell, a former monastery dating back to the mid-13th century. In keeping with its historic past, the dimly lit restaurant featured ancient vaults and thick brick walls. As I dug into a Skagen Toast, Roxie began her meal with a light concoction of bleak roe, sour cream and chopped red onion. I followed with a side of smoked pork confit boiled in beer and fennel cream, and Roxie, ready for a taste of the lake’s specialty, settled for a baked filet of char. This seemed an appropriate ending to a day full of history and good traditional food — enhanced by a bottle of Chablis Pinot Noir, all in the chiaroscuro light of a Rembrandt or Caravaggio painting. -

Övralid, Verner von Heidenstam’s last home by Lake Vättern.

Övralid, Verner von Heidenstam’s last home by Lake Vättern. -

Vadstena Castle

The next morning, eager to explore Vadstena, I visited the Sancta Birgitta Convent Museum and the Vadstena Castle. The museum elucidates the life and achievements of Birgitta, Scandinavia’s first and only saint. In one room, you’re invited to “converse” with Birgitta and browse through her heavenly revelations; in others you get glimpses of what life was like in the old nunnery. You also learn about the crusades, so popular in those days, along with the history of the Brigittine Order. I was a little surprised to discover that the Order ran the largest brewery in the country, producing 90,000 liters of beer a year, and that each nun received three liters a day for personal consumption.

King Gustav Vasa, who brought about the destruction of the convent while converting Sweden to Protestantism, also built the castle, thus retaining Vadstena’s prominence in Sweden. -

-

Surrounded by a moat and flanked by stout round towers, the castle, which began as a fortress when it was built in the mid-16th century, was later transformed into a continental-style Renaissance palace. Its heyday was apparently when Gustav’s son, King Johan III, lived there in the late 1500s. It never played much of a role in defending Sweden, nor as a royal residence, and for a long time it was used as a garrison and later as a granary and linen mill. More recently, however, much has been restored, and guided tours now show some of the grandeur of its early days. The Great Hall, the Lesser Hall, the Wedding Hall, some lovely tapestries, the Royal Steps … the list goes on. In one large hall was a display of opera costumes from various epochs, costumes which visitors can try on; they are part of an exhibit called “Opera on Hangers — the art of wardrobe at Vadstena castle.”

-

The Monastery Restaurant in Vadstena.

The Monastery Restaurant in Vadstena. -

By Bo Zaunders

-

Vadstena Castle.

Vadstena Castle. -

Read Part 2: Heading south toward Visingsö in the next issue of Nordstjernan

-

Vadstena Castle main entrance.

Vadstena Castle main entrance. -

-

-